INTO THE COSMIC ABYSS: HOW POE PREFIGURED THE BIG BANG

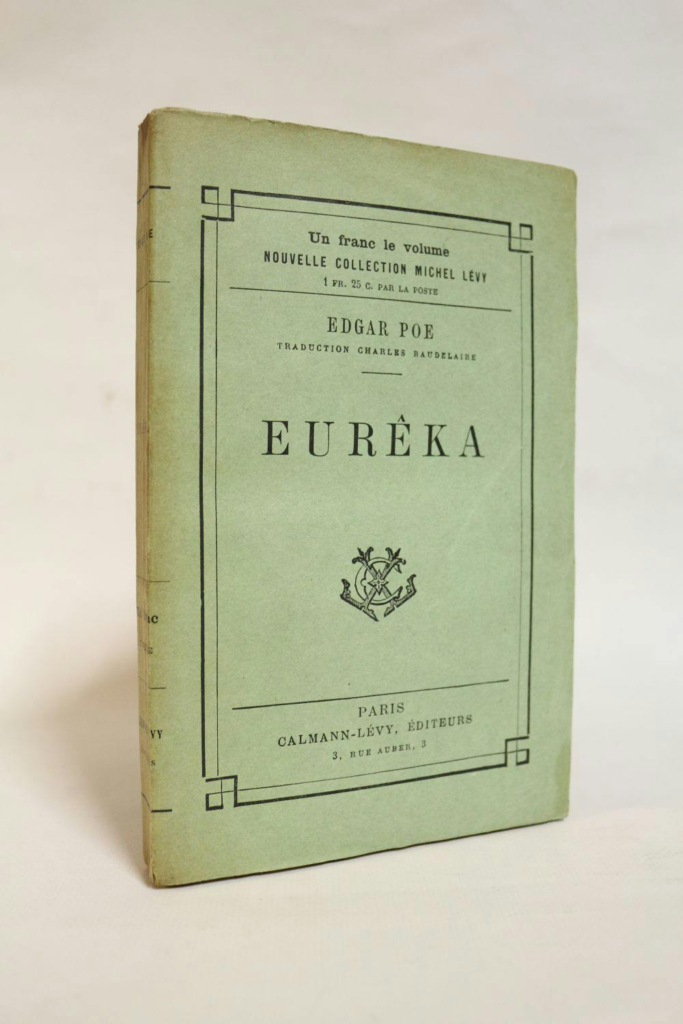

Beyond conjuring tales of mystery and imagination, Edgar Allan Poe harbored intense fascination with the workings of the universe. Though not a scientist himself, Poe’s enthusiasm for astronomy led him to intuit radical cosmic concepts before evidence emerged to support them. Most astonishingly, his 1848 prose poem Eureka depicted an explosive origin from a primordial “particle” – eerily echoing the modern Big Bang theory formulated decades later. While containing scientific errors, Eureka revealed Poe’s talent for deductive reasoning and prescient creativity.

A POETIC STARGAZER

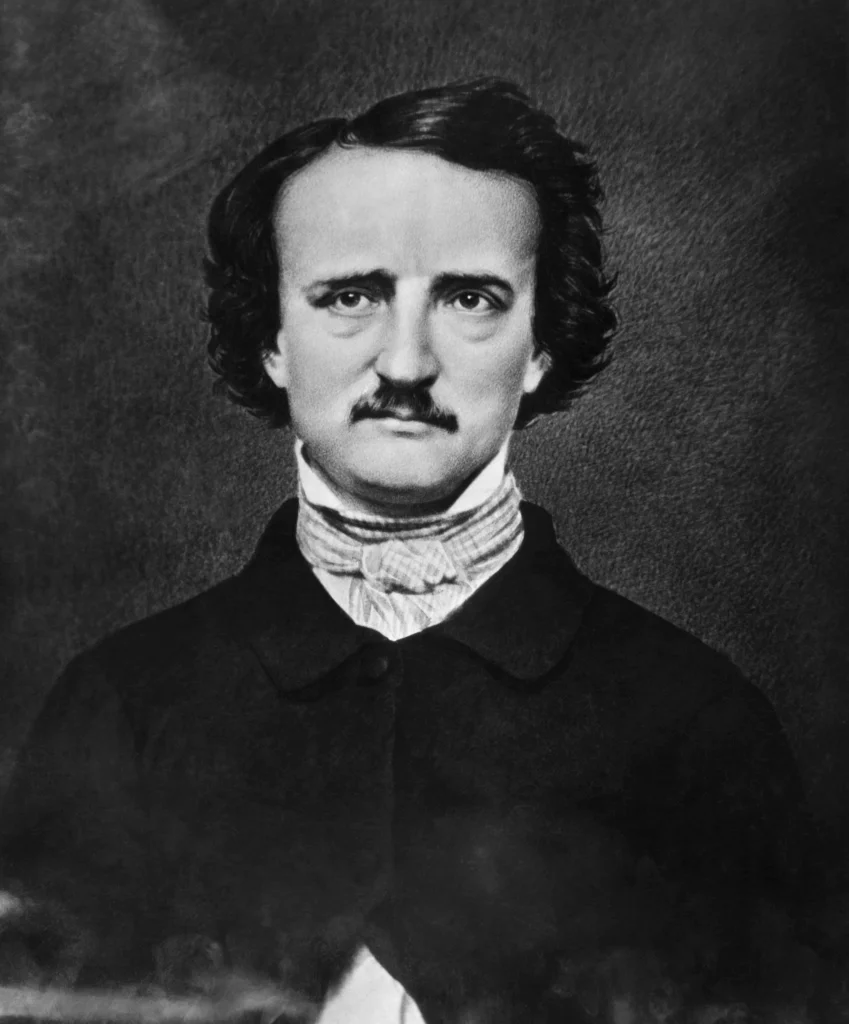

Edgar Allan Poe cemented his literary legacy through Gothic horror stories like “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Fall of the House of Usher.” His grim poetry in works like “The Raven” defined Poe as a master of the macabre. Yet beyond the melancholy of his fiction and verse, Poe nurtured a second passion – musing on the mysteries of the universe.

Though lacking any formal scientific training, Poe devoured books on astronomy and physics. He occasionally inserted references to celestial marvels into stories. Poe saw breathtaking beauty in the heavens and incorporated his love and fascination of the cosmos into his writings.

When not writing tales of gloom, Poe enjoyed stargazing from his home’s porch and contemplating enigmas like the true nature of the Milky Way. Though amateurish, his curiosity fueled speculations about the cosmos that proved uncannily forward-looking.

OLBERS’ PARADOX AND A DARK SKY

One puzzle vexing astronomers in Poe’s era was first noted in 1823 by German scientist Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers. Known as “Olbers’ paradox,” it asked why the night sky appeared dark if the universe was eternal and infinitely large. Wouldn’t every vista be filled with the accumulated light of countless stars? If the universe is infinite, every dot in the sky should have a star and that star’s light should be reaching our eyes and because of this the whole night sky should be lit up with starlight, turning night into day.

Poe was intrigued by this “riddle of the heavens” and offered an ingenious solution in Eureka. He posited that the universe must be finite in space and time – that most stars were simply too far for their light to have reached Earth yet. By suggesting the cosmos had a beginning, Poe avoided the conclusion of an infinitely bright night sky that stumped other theorists.

Modern astrophysics proved Poe right. The Big Bang theory explains the darkness between stars as regions where light hasn’t had time to travel over cosmic history. Poe correctly deduced that the universe must be constrained by distance and its origins. His insight was remarkable and broke the perceptions of a boundless, perpetual cosmos centered on the Earth.

ENVISIONING COSMIC EXPANSION

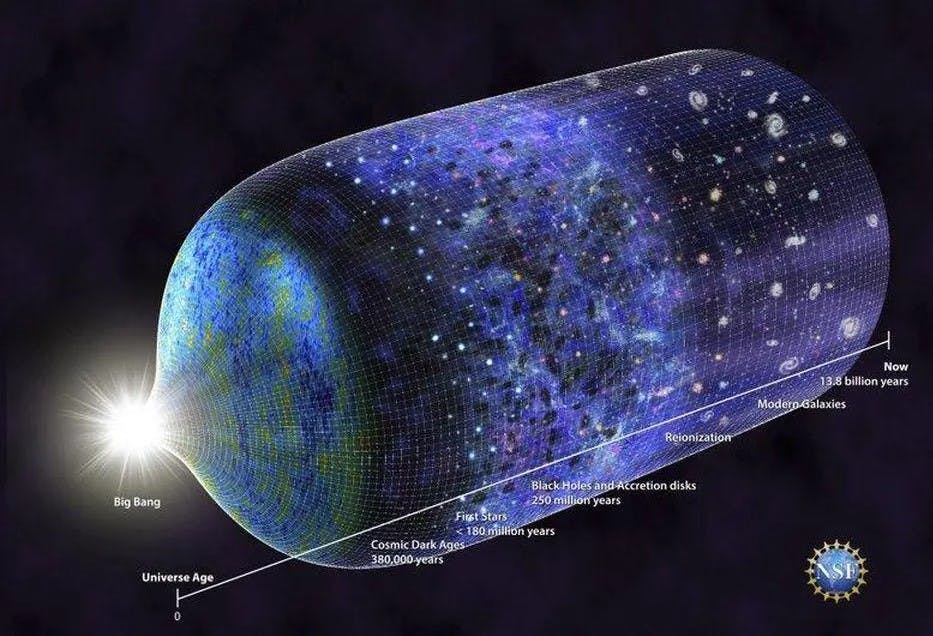

Poe also perceived that the universe was expanding, anticipating evidence discovered decades later. In Eureka, he wrote of matter forming distinct celestial objects that “are now rushing onwards, in all directions, towards their own general centre.” This implied a past union that exploded outward, carrying bodies like stars apart across deepening space.

The idea of an expanding universe didn’t gain mainstream acceptance until the 1920s and 1930s, following solutions to Einstein‘s equations and later observations by astronomers like Edwin Hubble. Poe lacked empirical data or mathematical formulas. But through sheer deductive logic, he envisioned the cosmos growing larger over time. This marked a dramatic shift from the static universe model that prevailed when Poe lived.

By reasoning through thorny problems, Poe overcame notions of an infinite, unchanging night sky. A universe with a dynamic history of growth and change aligned better with observations. Once again, Poe’s speculations anticipated revelations through more systematic science.

THE PRIMORDIAL “PARTICLE”

Perhaps Poe’s most startling insight was conceptualizing a dramatic cosmic origin he called “one instantaneous flash.” In Eureka, Poe wrote:

“Let us now endeavor to conceive what Matter must be, when, or if, in its absolute extreme of Simplicity. Here the Reason flies at once to Imparticularity – to a particle – to one particle – a particle of one kind – of one character – of one nature – of one size – of one form.”

He went on to describe how the primordial “particle” explosively spawned countless atoms spreading through space from a central point. This resembled the modern Big Bang theory’s explanation of cosmic evolution from a hyper-dense, uniform beginning into myriad forms.

Published in 1948, Poe’s explosive creation concept predated evidence for a Big Bang origin by over a century. While other thinkers believed the universe was eternal, Poe saw compelling reasons to infer a dramatic birth. Through creative extrapolation, he glimpsed traces of cosmic truth before science could document them.

In modern cosmology the idea of a ‘singularity’ or a primordial particle at the beginning of the universe is no longer an accepted model since requires ‘initial conditions’ to explain the birth of the universe. Our observations which include the uniform temperature of the cosmos, and lack of magnetic monopoles, among others are more in-line with the Inflationary Model of the Big Bang, where the early universe went through a exponential growth. The exponential growth part posits that there was no singluarity, but that we currently don’t have enough information on how or if ever inflation started.

LIMITATIONS OF AN AMATEUR

For all his brilliance, Poe’s Eureka also contained misguided notions. He rejected Newtonian gravity, saw energy and matter as indestructible, and made errors regarding the motion of planets. As a lay enthusiast, Poe lacked the expertise and mathematical discipline to build fully coherent theories.

Poe erred in seeing the universe itself as a kind of organism that had developed from chaos into increasing order and would culminate in a “final embrace” as all matter collapsed together. Modern physics sees cosmic expansion as endless and not teleological.

But Poe’s grandest mistakes arose from an absence of data, not failures of intellect. He reasoned ingeniously from first principles and the limited astronomy of his day. Modern scientists with advanced telescopes and computers have since constructed far more detailed models.

INTUITION BEFORE EVIDENCE

The aspects of Eureka aligning with later discoveries testify to Poe’s imagination and deductive skills rather than any mystical powers. Brilliant leaps often precede formal proof in science. Poe intuited deep truths about the universe from philosophical arguments rather than through rigorous tests.

In many cases, math caught up to confirm Poe’s conjectures. The marked brilliance of Eureka was conceiving concepts like a finite, expanding universe and a primordial bang when prevailing beliefs leaned against them. Like politics or art, science benefits from visionaries who re-envision boundaries of the possible.

While obscure in his day, Poe’s cosmic speculations were an astonishing feat of intellectual adventure. They reveal the power of questioning orthodoxies and following reason wherever it leads. More than sheer luck, Eureka was the achievement of a free intellect unshackled by convention or dogma. Poe’s poetic musing uncovered hints of cosmic realities taking shape.

FROM HORROR WRITER TO UNIVERSE BUILDER

For devotees of Poe’s chilling stories, Eureka seems a jarring departure. Far from noir fantasies, it finds Poe crafting sweeping myths of creation. Yet the work fused many signature aspects of his writing into an idiosyncratic scientific saga.

Poe brought poetic language, intuition, and imagination to a technical realm where they were in short supply. Eureka became the arena where Poe’s empirical and artistic sides met. He proved that science, from Darwin to Einstein, needs audacious conjecture to unlock mysteries beyond current understanding. The tools of an author – creativity and deduction – helped Poe grasp timeless enigmas.

No mere pseudoscience, Eureka exemplified Poe’s resistance to false constraints on thought. Its deductive riches testify to the power of intellect unleashed.

RESISTANCE AND REDEMPTION

In Edgar Allan Poe’s lifetime, Eureka suffered ridicule and neglect. Theorizing way beyond his depth, critics thought, the amateur poet had indulged in flimsy speculation masquerading as knowledge. Poe’s publisher warned the work would be used against him by his enemies. Critics derided it as “hyperbolic nonsense” filled with “scientific phrase—a mountainous piece of absurdity”. Even Poe’s friends were offended, with one calling it “a damnable heresy”. Some found Eureka simply too dense and lengthy.

Yet Poe staunchly defended his work, considering it his masterpiece. He believed Eureka would “immortalize him” centuries later once proven accurate. In a letter, Poe wrote: “I have no desire to live since I have done Eureka. I could accomplish nothing more.” Poe died a little over a year after Eureka’s publishing.

Though initially rejected as pseudoscience, some contemporaries did recognize its merits. Albert Einstein later praised Eureka as the “beautiful achievement of an unusually independent mind.” No reader can doubt Poe threw his full passion into exploring time and space.

CLUES TO OUR COSMIC HOME

Like an ancient map filled with legends, Eureka mixes wisdom, mystery, and myth. While not literal truth, its content help expand cultural imagination. Poe opened doors to possibilities beyond what instruments could confirm.

There is genius in Poe’s willingness to probe the unfathomable. He embraced what Jules Verne called “the unknown and the infinite,” defending theories that struck others as radical or bizarre. By approaching the universe itself as a grand creative work, Poe ennobled science through the lens of human creativity. The cosmos holds more wonders than our philosophies can fathom.

Additional Facts

Additional Facts

18

Edgar Allan Poe was 18 years old when he published his first book “Tamerlane and Other Poems” in 1827. There are currently only 12 copies that are said to exist.

$9

Poe’s best known work is the dark poem “The Raven,” for which he was paid $9 by the literary magazine The American Review. The poem was published in February of 1845. The poem was published under a pseudonym “Quarles” and not as Edgar Allan Poe.

70 Years

For 70 years an unknown person dubbed “Poe Toaster” would leave a bottle of Cognac and three red roses on Poe’s grave every year on January 19th. The person would be dressed in black and wearing a white scarf and a large hat. This tradition mysteriously ended in 2009 and the identity of the “Poe Toaster” still remains a puzzle.