THE GREAT HORSE MANURE CRISIS THAT WASN’T

In the late 1800s, cities faced a smelly crisis that seemed unsolvable. Streets were choking on the massive quantities of manure left behind by the thousands of horses essential for transport and shipping. With no solution in sight, some declared that urban civilization was doomed to be smothered in horse waste. Yet the great manure calamity never came to pass, offering a cautionary tale about crying doom too readily. Lets get into the Horse Dung Dilemma of 1894.

A CITY DROWNING IN DUNG

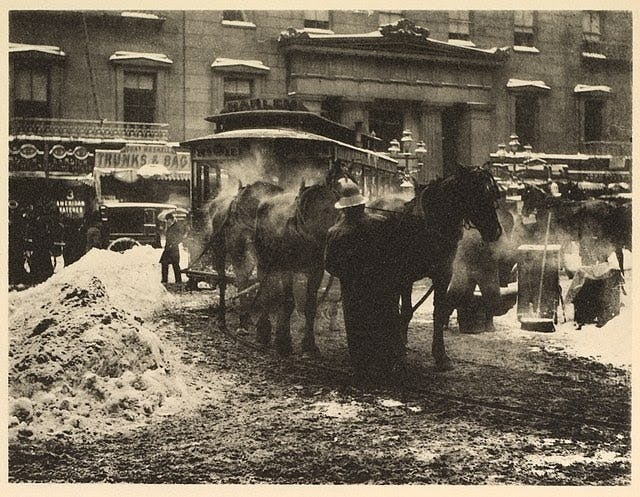

In 1894, life in thriving metropolises like London and New York City centered around horses. Long before cars, people relied on hansom cabs and omnibuses pulled by teams of horses to get around. Freight wagons and drays drawn by the animals transported produce, parcels, and goods across muddy streets.

London’s 11,000 cabs and several thousand buses each needed fresh horses working in shifts to operate. This added up to over 50,000 horses transporting Londoners daily. Meanwhile, New York’s 100,000+ horses produced nearly 2.5 million pounds of horse dung and 10 million gallons of urine per day.

As cities expanded, ever more horses were pressed into service, which created a messy crisis. Horse manure and carcasses accumulated on streets, along with thriving flies that spread disease. The noxious issue grew into a public health nightmare.

DOOMSDAY PREDICTIONS

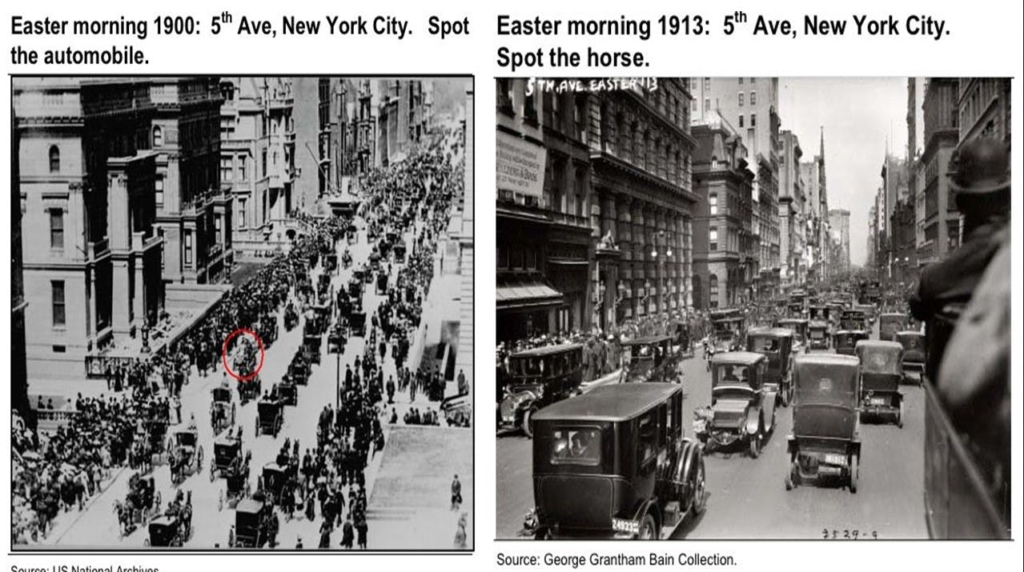

In 1894, the Times of London gloomily predicted that within 50 years every street would be buried under 9 feet of manure. The situation seemed dire, especially when the first urban planning conference held in 1898 ended abruptly after failing to generate solutions.

With horse numbers and horse dung increasing and land for disposal shrinking, bacteria-laden manure was creating intolerable urban environments. The crisis laid bare the limits of planning in rapidly growing cities. There seemed no way for public health, transit, and sanitation to keep pace with booming populations and inadequate infrastructure.

Humorists joked that cities would need to construct second or third stories for their sidewalks. With no relief in sight, many saw the writing on the wall – urban civilization faced an existential threat from horse waste accumulating unchecked.

CRISIS SPURS INNOVATION

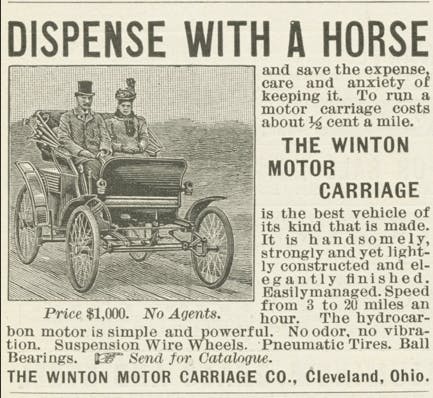

Necessity is the mother of invention, and the manure predicament sparked new thinking. Rising costs of feeding, housing, and disposing of waste forced innovation in street transit. Electric trams and motorized buses gradually replaced horse-drawn transport.

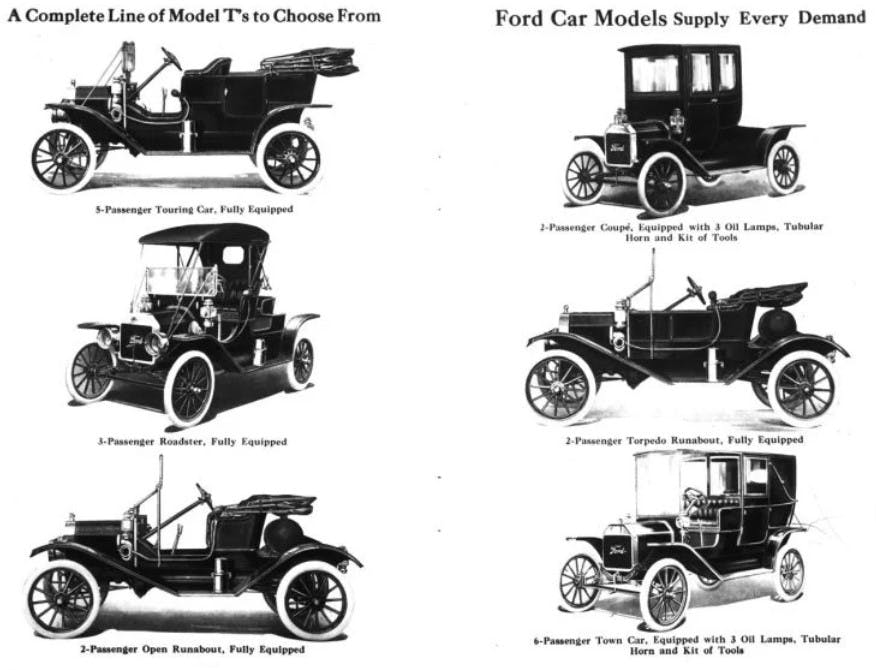

But the real solution galloped in as Henry Ford’s automobile assembly line debuted the Model T – the first affordable car for many families. As cars became accessible to the middle class, public interest shifted from public to private transport. Cities eagerly paved over cobblestone streets to accommodate automobiles.

Within decades, cars outnumbered horses even in congested Manhattan. The last horse-pulled streetcar was retired in 1917. Practically overnight, the manure problem vanished as horses were replaced. Long-predicted urban collapse was avoided through technology and changing habits.

PANIC PEDDLING?

In hindsight, manure panic seems short-sighted. But grave concerns were valid, given knowledge and tools available in the late 1800s. With cities rapidly expanding and infrastructure agging, public health risks were real.

However, critics note that declared inevitable disasters often fail to account for society’s ability to adapt. Human ingenuity will usually create solutions if given the right incentives and freedom to respond. Innovation and changing attitudes, not centralized planning, alleviated the waste crisis.

Of course, cars brought their own headaches in pollution, traffic, and suburban sprawl. But they stimulated American industry and offered personal freedoms. trade-offs still debated today.

COMPLACENCY’S RISKS

Does the manure miscalculation hold lessons today? Alarmist language pervades issues like climate change, warning of civilizational collapse if trends continue unchecked.

Perhaps crises seem more insoluble in modern society. But declaring defeat through projections invite self-fulfilling prophecies. People may abandon hope and feel helpless in the face of supposed inevitabilities.

This mindset can become justification for restrictive policies that curb freedoms and imperil open inquiry. Yet breakthroughs often emerge from unplanned corners. Brilliant solutions start with believing they exist.

The manure panic shows even trends that appear inexorably disastrous can reverse through human ingenuity. But this relies on preserving conditions where inspiration can flourish, not smothering society in defeatism.

Future shocks will emerge. But civilization has overcome seemingly existential threats before, like mountains of manure filling London’s streets. Rather than Fearmongering figuratively and literally, faith in creative spirit may drive solutions.

THE NEXT CRISIS CATALYST?

What modern “manure crisis” is awaiting an unforeseen breakthrough? Climate change, environmental pollution, sustainable energy sources, and emerging technologies like AI all pose complex challenges, but frameable as existential threats.

Perhaps hydrogen provides a cleaner fuel alternative. Or lab-grown meat eliminates factory farming. Or carbon capture progresses beyond infancy. An obscure patent application today may contain the seed of resolution, like Carl Benz’s 1886 “vehicle powered by a gas engine” that ushered in motoring.

But the seeds of great inventions only flourish in fertile ground. Problem-solvers require economic and intellectual freedom to experiment and spread concepts. Even ideas that seem eccentric or unrealistic merit exploring without stigma.

The lessons of the manure panic are that challenges viewed as insurmountable can disappear nearly overnight, and stagnation arises only when imagining better futures ceases. With openness and courage, society can clear paths through the thorniest modern problems as innovators once cleanly swept horse droppings into history’s dustbin.

170,000

In 1900 there were approximately 170,000 horses in New York City, while some sources estimate around 200,000. 3.5 million New Yorkers at the time used these horses to move around town.

$650

Olds Motor Works sold 425 of their gasoline powered “curved dash runabout” for $650 each. Four years later they had sold 19,000 making it the first commercially successful American car.