TRAGEDY THAT SPARKED REFORM

At quitting time on March 25, 1911, a spark caught in a scrap bin on the eighth floor of the Asch Building in New York’s Greenwich Village. The bin sat in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, a bustling garment workshop employing hundreds of immigrant youths. In minutes, the fire raged out of control, sending panicked workers scrambling toward locked exit doors. Trapped victims soon faced a horrific choice – die by flames or jump nine stories to concrete pavement far below…

This unfathomable disaster, killing 146 workers, fundamentally transformed the nation’s approach to workplace hazards. The shocking images of young seamstresses leaping to their deaths seared America’s conscience. From the ashes emerged a citizen movement demanding government action and corporate accountability when profits trump safety.

Join us as we revisit this watershed tragedy through the eyes of those who perished, those who escaped, and those still fighting so such horrors never repeat. For the Triangle Fire revolutionized urban building codes, catalyzed workplace reforms nationwide, and fueled the labor movement – cementing industrial injustice as a catalyst for progress.

THE RISE BEFORE THE FALL

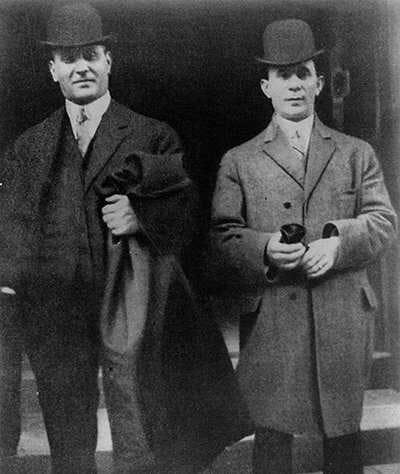

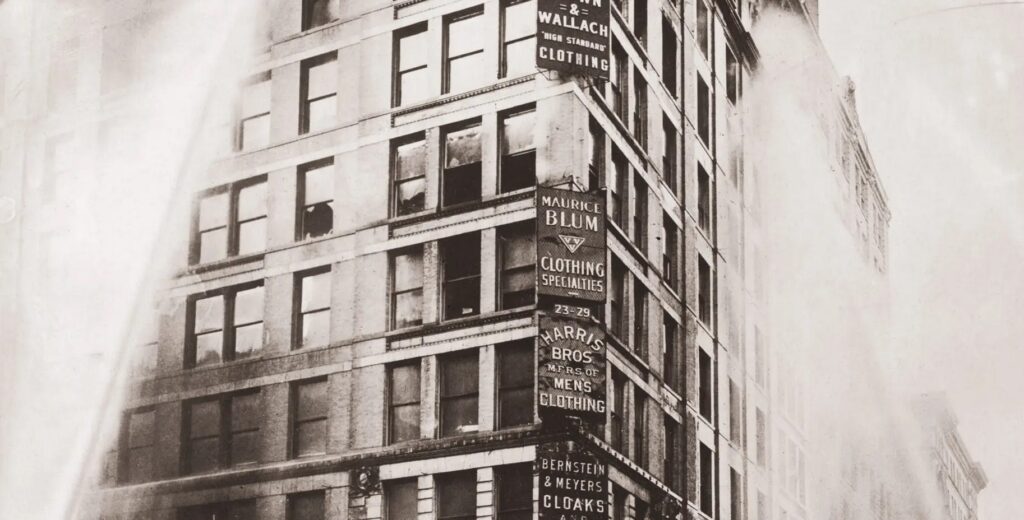

In 1900, entrepreneurs Max Blanck and Isaac Harris capitalized on New York’s booming garment industry by founding the Triangle Waist Company. Early success led the partners to lease the top three floors in Greenwich Village’s modern 10-story Asch Building by 1909. Outfitting the space with rows of sewing machines, the factory grew to employ over 500 workers – mostly immigrant women and girls as young as 14.

Courtesy: Cornell Kheel Center

Laboring six days a week in cramped quarters, seamstresses pieced together ladies’ blouses popularized by swelling ranks of working women. The “shirtwaist” crossed class lines – suitable for factory shifts or middle-class meetings. Though some employees joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, Triangle remained non-union – with owners vigilant toward labor organizers.

Behind the scenes, Blanck and Harris maximized profits by skirting fire safety. Exit doors were locked to prevent theft, scraps piled dangerously high. Crowded conditions, bare windows, and vacant fire hoses evaded inspections through the owners’ political connections. But one oversight upended their booming enterprise, exposing lax standards citywide.

INFERNO ENGULFS THE ASCH BUILDING

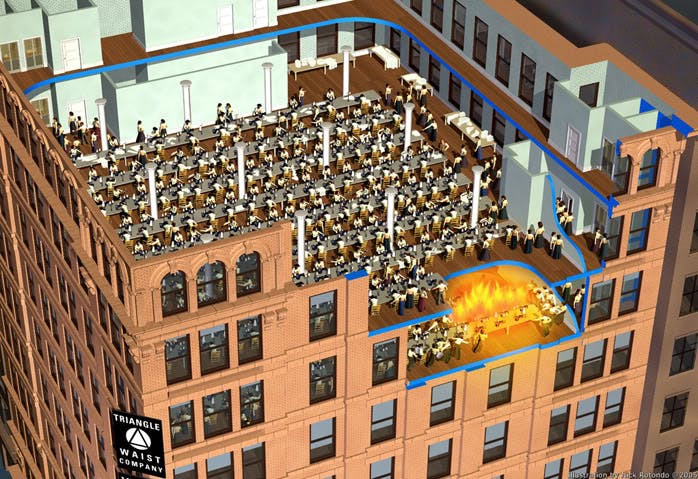

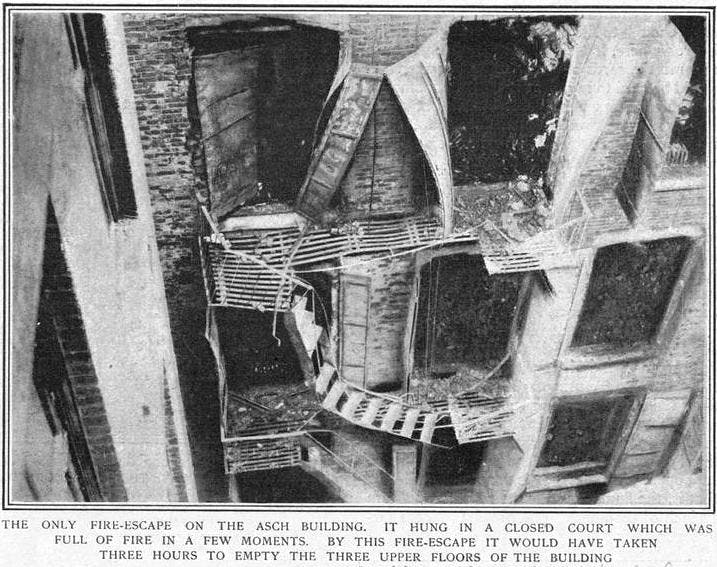

The first spark of the Triangle Fire erupted just before closing on March 25th – likely a worker’s discarded cigarette igniting scraps in a cutter’s bin. Flames quickly leapt to fabrics overhead, turning the abandoned eighth floor into a tinderbox. As smoke billowed between loft ceilings, panicked workers on upper levels rushed toward stairwells and freight elevators while others scrambled onto external fire escapes.

With no way out the ninth floor’s locked exit, terrified employees crammed at windows as the factory became “a mass of traveling fire” according to a fire captain. Charred bodies soon plunged toward the sidewalks below.

“I learned a new sound,” recounted reporter Bill Shepherd, “the thud of a speeding, living body on a stone sidewalk. Thud-dead, thud-dead, thud-dead…” In just 15 minutes, 146 workers – mostly women – perished either by flames, smoke, or desperate leaps into the abyss.

NYPL Collection

Blasting news headlines centered victims plummeting hand-in-hand nine stories – Belle Stein and Rosie Oringer died embracing life-long friends. Reports wrongly assumed owners tossed valuable cloth bolts out windows. By day’s end, New Yorkers finally comprehended the awful truth.

REFORM MOVEMENT FORGED BY OUTRAGE

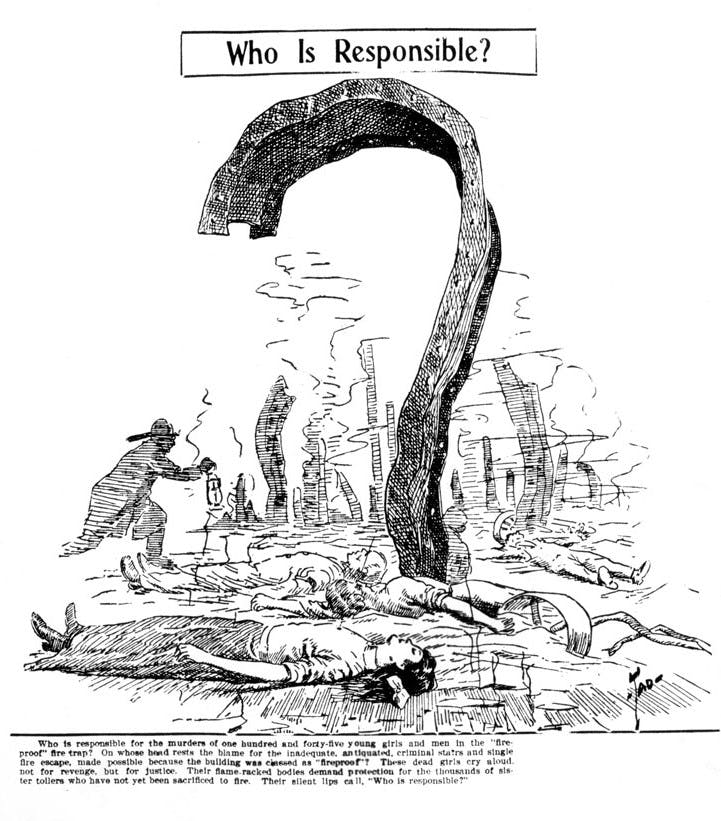

Initial reactions followed a grieving script – flowers piled high alongside citizens united in mourning the innocent dead. But sorrow soon turned toward outrage over preventable hazards enabling mass death. Reformers wasted no time targeting lax regulations that valued profit over workers’ safety – beginning in progressive New York.

Within days, local unions organized a funeral march attracting over 100,000 participants. Labor activists pressed authorities to charge Triangle owners with manslaughter over the locked doors trapping seamstresses. District Attorney Charles Whitman himself interviewed witnesses, vowing to hold the factory’s leadership fully accountable.

After grand juries indicted Blanck and Harris, their high-priced attorney Maurice Steuer managed an acquittal by savvily questioning fire marshal testimony. Though controversy erupted over the verdict, the owners finally settled civil suits in 1914 – paying victims’ families $75 per life lost.

National Archives, General Records of the Department of Labor

NATIONAL RECKONING SPURS REFORM

Despite the legal defeat, Triangle provoked a national reckoning over industrial hazards – one that public figures skillfully pressed toward lasting change. Officials like State Senator Robert Wagner conducted exhaustive research documenting workplace dangers requiring government remedies. Horrific imagery from the disaster also aided reformists championing enhanced building codes and improved emergency response.

Most prominent was Frances Perkins, an eyewitness to the 1911 tragedy with a vantage point etching searing details into memory. Her account of women embracing death rather than burn alive catalyzed a 40-year mission championing progressive labor reforms across roles culminating as FDR’s Secretary of Labor. The movement pioneered breakthroughs like the minimum wage, child labor limits, accident insurance, pensions, and the 40 hour week itself.

According to Perkins, the outrage unleashed on March 25, 1911 ignited public will for sweeping workplace upgrades that seeds the modern safety net. She deemed it a catalyst event birthing policies we now consider fundamental worker rights.

LEGACY STILL UNFOLDING

Over a century later, the Triangle Fire’s legacy continues evolving alongside America’s complex relationship with workplace equity and security. For many, the silently falling smoke victims remain icons of corporate greed murdering vulnerable employees. Their memory surfaces whenever new industrial disasters reveal that still too little protects society’s most desperate workers.

In honoring Triangle’s victims, labor activists keep alive hopes for empowering reforms ahead, just as their predecessors channeled horror into progress generations ago. Perhaps the lasting message is acknowledging how citizen movements can lead government, not the reverse, whenever conscience cannot abide injustice.

And once again from the ashes, a model arises on how even the starkest tragedies might sow redemption’s seeds – if they inspire solidarity and acts of conscience when they matter most. For flames charring the Asch Building fueled slow-burning fires of social change still lighting the long march toward workers’ dignity today.