Imagine a spot on Earth so remote that your closest human neighbors are astronauts. A place where the nearest land lies nearly 1,700 miles away in any direction, and the waters below harbor less life than almost anywhere else in the world’s oceans. This is Point Nemo or Punto Nemo, the oceanic pole of inaccessibility—our planet’s most isolated location, where separation from humanity reaches its absolute maximum.

The Quest for Ultimate Remoteness

The story of Point Nemo begins with what scientists call “the longest-swim problem”: If you had to drop someone in the ocean at the point farthest from any land, where would that spot be? This mathematical puzzle remained unsolved until 1992, when Croatian-born engineer Hrvoje Lukatela decided to tackle it with his sophisticated mapping software.

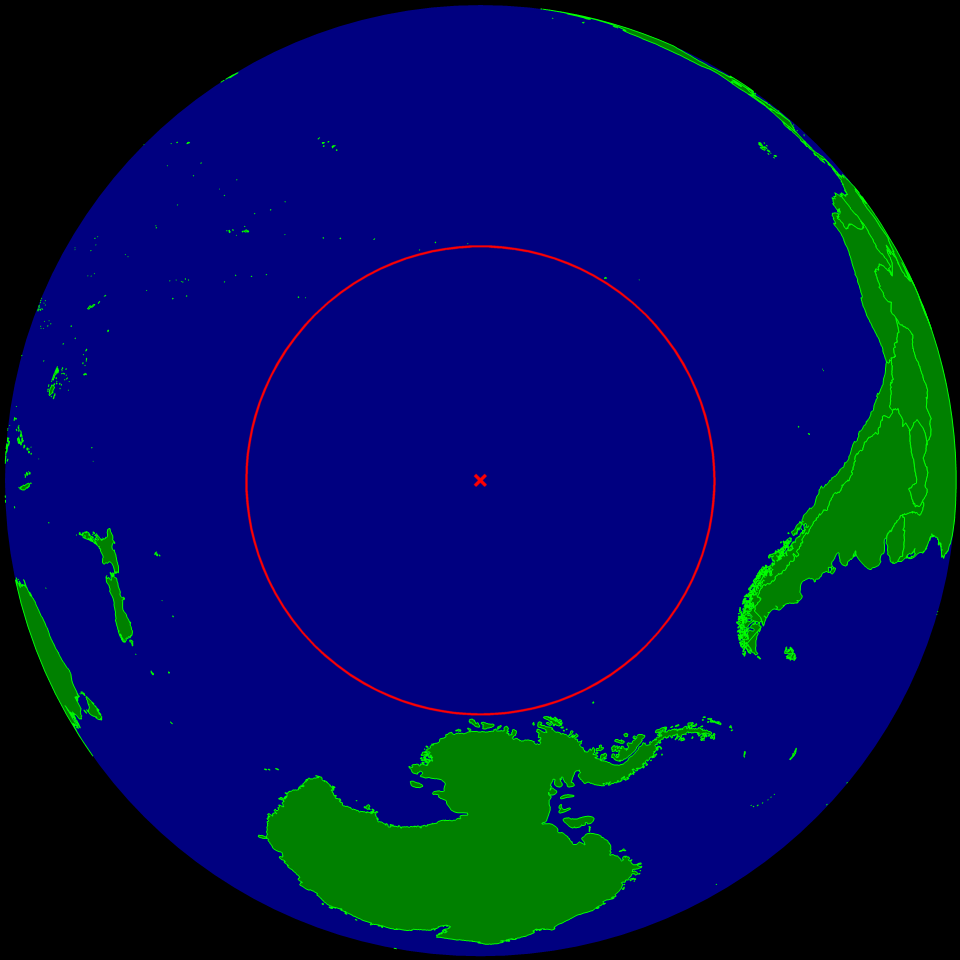

What Lukatela discovered was a precise location in the South Pacific: 48°52.6′ south latitude and 123°23.6′ west longitude. This spot sits at the center of a circle defined by three distant points of land: Ducie Island in the Pitcairn Islands to the north, Motu Nui near Easter Island to the northwest, and Maher Island off Antarctica to the south. Each of these outposts lies exactly 1,670.4 miles from Point Nemo—roughly the distance from Manhattan to Santa Fe.

A Marine Desert in Earth’s Greatest Ocean

The waters around Point Nemo hold a curious distinction: they are among the most lifeless in the world’s oceans. Due to its location within the South Pacific Gyre, the area lacks the nutrient-rich upwellings that support abundant marine life elsewhere. The water here is remarkably clear—a beautiful but stark testament to its biological poverty.

The region’s isolation extends beyond mere distance. No commercial shipping lanes cross these waters. No countries maintain naval presence here. The vast expanse of ocean around Point Nemo lies beyond any national jurisdiction, making it truly a place where, as its namesake Captain Nemo from Jules Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” might say, one recognizes no superiors.

Where Space Meets Sea

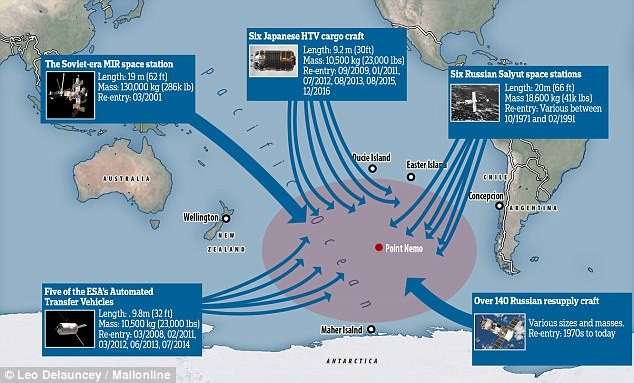

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Point Nemo is its unlikely connection to space exploration. The spot has become Earth’s unofficial spacecraft cemetery, the final resting place for hundreds of decommissioned satellites, space stations, and other orbital debris. When space agencies need to bring down large spacecraft, they aim for these remote waters to minimize any risk to human populations.

The remains of the Russian space station Mir lie somewhere in these depths, along with pieces of more than 250 other spacecraft from various space agencies and private companies. In a poetic twist, the closest humans to Point Nemo are often the astronauts aboard the International Space Station, passing overhead at an altitude of about 250 miles—far closer than any person on Earth.

Scientific Expeditions to Nowhere

Despite—or perhaps because of—its remoteness, Point Nemo has attracted the attention of scientists seeking to understand our planet’s most isolated ecosystem. In 2019, a research expedition aboard the JOIDES Resolution ventured into these waters to study the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the world’s most powerful ocean current that helps regulate global climate.

The journey wasn’t easy. The vessel faced the notorious weather of the Southern Ocean, where waves can reach heights of 60 to 70 feet and violent storms the size of Australia can force ships to flee. Yet the scientific team, led by oceanographer Gisela Winckler, managed to extract valuable sediment cores from the ocean floor, revealing millions of years of climate history.

From Fiction to Reality

Point Nemo’s name comes from Jules Verne’s misanthropic submarine captain, but its literary connections don’t end there. The location has captured imaginations far beyond the scientific community. H.P. Lovecraft placed his sunken city of R’lyeh, home to the cosmic entity Cthulhu, near these coordinates. More recently, the virtual band Gorillaz based their album “Plastic Beach” around a fictional landmass at Point Nemo.

A Mirror to Human Impact

Even here, at Earth’s most remote location, humanity’s influence can be detected. Scientists sampling these waters have found microplastics—tiny particles of human-made debris that have reached even this far-flung corner of the planet. It’s a sobering reminder that in the modern world, true isolation may no longer exist.

The region also serves as a crucial monitoring point for climate change. Recent studies of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current near Point Nemo have revealed concerning changes in its behavior. The current is warming and speeding up, shifting southward in ways that could accelerate the erosion of Antarctic ice.

The Future of Nowhere

Point Nemo’s significance continues to grow. As space exploration advances, more defunct satellites and spacecraft will find their way to this remote graveyard. The International Space Station itself is scheduled to join them in 2031, marking the end of an era in human space exploration.

As we push the boundaries of both space and ocean exploration, Point Nemo stands as a reminder of our planet’s vast scales and continuing mysteries. It represents a peculiar intersection of human achievement and ultimate remoteness—a place where our space-faring ambitions meet the most isolated waters on Earth.

For the few who have passed nearby, like the crew of the racing yacht Mālama during the Ocean Race, Point Nemo offers a rare perspective on human existence. As navigator Simon Fisher described it, there’s “something very special about knowing you’re someplace where everybody else isn’t.” In our increasingly connected world, such places of profound separation become all the more remarkable.

Whether viewed from the deck of a research vessel, the cockpit of a racing yacht, or the cupola of the International Space Station, Point Nemo remains a testament to Earth’s capacity to humble us with its vast expanses. It reminds us that even in an age of global connectivity and constant communication, our planet still holds places of extraordinary isolation—spots where the horizon stretches empty in every direction, and the nearest humans are not on Earth at all, but floating among the stars.