In the winter of 1887, Parisian journalists gathered at a curious construction site on the Champ de Mars. There, amid wooden scaffolding and the rhythmic clang of hammers, they witnessed what one reporter would describe as men “reaping lightning bolts in the clouds.” These workers, perched on narrow ledges, were assembling what would become the most controversial—and ultimately most beloved—structure of the 19th century: the Eiffel Tower. Lets dive into how the Eiffel Tower was built.

The Vision Takes Shape

The story begins with a competition. As France prepared to celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution with the 1889 World’s Fair, organizers sought a monument that would showcase French engineering prowess. The brief was ambitious: create a 300-meter iron tower—a height equivalent to the symbolic figure of 1,000 feet, nearly twice as tall as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Among 107 submitted proposals, one stood out. It came from the office of Gustave Eiffel, already famous for his innovative bridge designs. But the true originators of the concept were two of his chief engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, who first sketched their idea in June 1884. Their initial design was stark—a giant pylon of latticed girders that would taper as it rose.

Recognizing that pure engineering might not capture the public imagination, they enlisted architect Stephen Sauvestre to refine the tower’s appearance. Sauvestre added decorative arches at the base, glassed-in floors on each level, and other ornamental elements. While many of these flourishes were eventually simplified, the grand arches remained, giving the tower its distinctive silhouette.

Building the Impossible

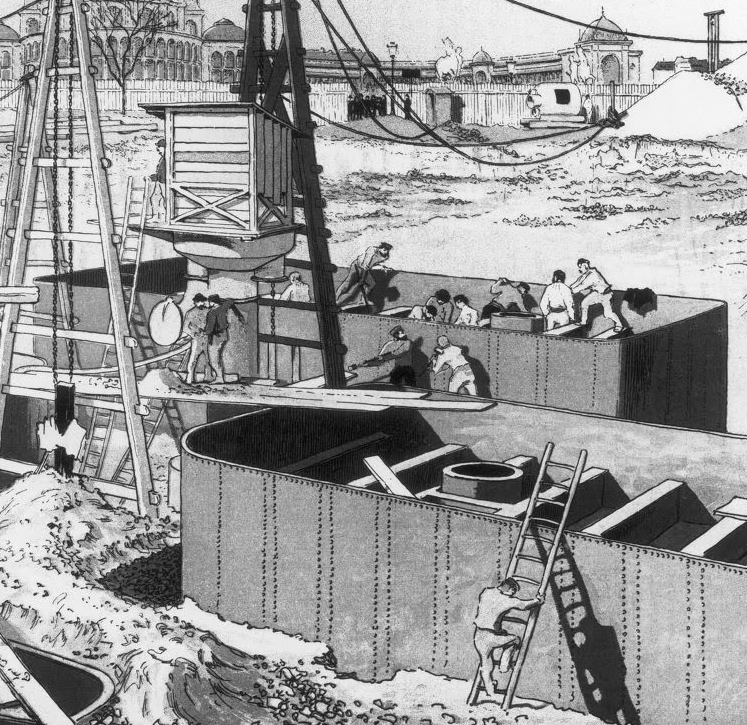

Construction began on January 26, 1887, starting with the tower’s foundations. This first phase was critical—each corner of the tower would exert enormous pressure on its supporting block. On the Seine side, workers used watertight metal caissons and compressed air to work below the water level, laying the groundwork for the massive structure above.

The assembly itself was a masterpiece of precision. The tower’s 18,038 iron parts were fabricated at Eiffel’s workshop in Levallois-Perret, just outside Paris. Each piece was calculated and traced to an accuracy of one-tenth of a millimeter. These components would be joined by 2.5 million rivets, requiring a coordinated dance of skilled workers.

A team of four men handled each rivet: one to heat it, another to hold it in place, a third to shape the head, and a fourth to beat it with a sledgehammer. As journalist Emile Goudeau observed during a site visit in early 1889: “One could have taken them for blacksmiths contentedly beating out a rhythm on an anvil in some village forge, except that these smiths were not striking up and down vertically, but horizontally.”

The workforce ranged from 150 to 300 workers, many of them veterans of Eiffel’s bridge projects. They used wooden scaffolding and small steam cranes that climbed the tower as it grew, utilizing the runners that would later house the tower’s elevators. Sand boxes and hydraulic jacks allowed for positioning of metal girders with millimeter precision.

The Art of Engineering

What appears to be a simple tapering form actually embodies sophisticated engineering principles. The tower’s curved shape isn’t just aesthetic—it’s mathematically determined to offer optimal wind resistance. As Eiffel himself explained, “All the cutting force of the wind passes into the interior of the leading edge uprights.”

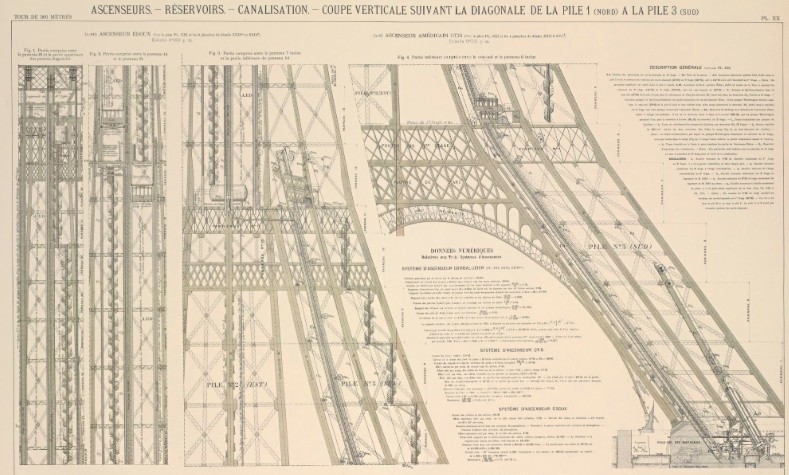

One of the most innovative features was the elevator system. The tower’s curved legs presented a unique challenge—the elevators would need to ascend at changing angles, starting at 54 degrees and leveling to 78 degrees at the top. The solution came from the Otis Elevator Company, which designed glass-caged machines with rotating seatbacks to adjust to the varying angles.

Fighting for Acceptance

While the engineering was revolutionary, not everyone appreciated this revolution. In February 1887, a group of prominent artists and writers published a scathing protest in Le Temps newspaper. Charles Garnier, Alexandre Dumas fils, and others denounced the “gigantic black factory chimney” that would crush “our humiliated monuments.”

Eiffel’s response was both passionate and prescient. “Because we are engineers,” he wrote, “does one assume that beauty does not concern us in our constructions?” He argued that the tower’s mathematical curves would create “a strong impression of strength and beauty,” and that there was “in the colossal, a unique attraction and charm to which ordinary artistic theories are hardly applicable.”

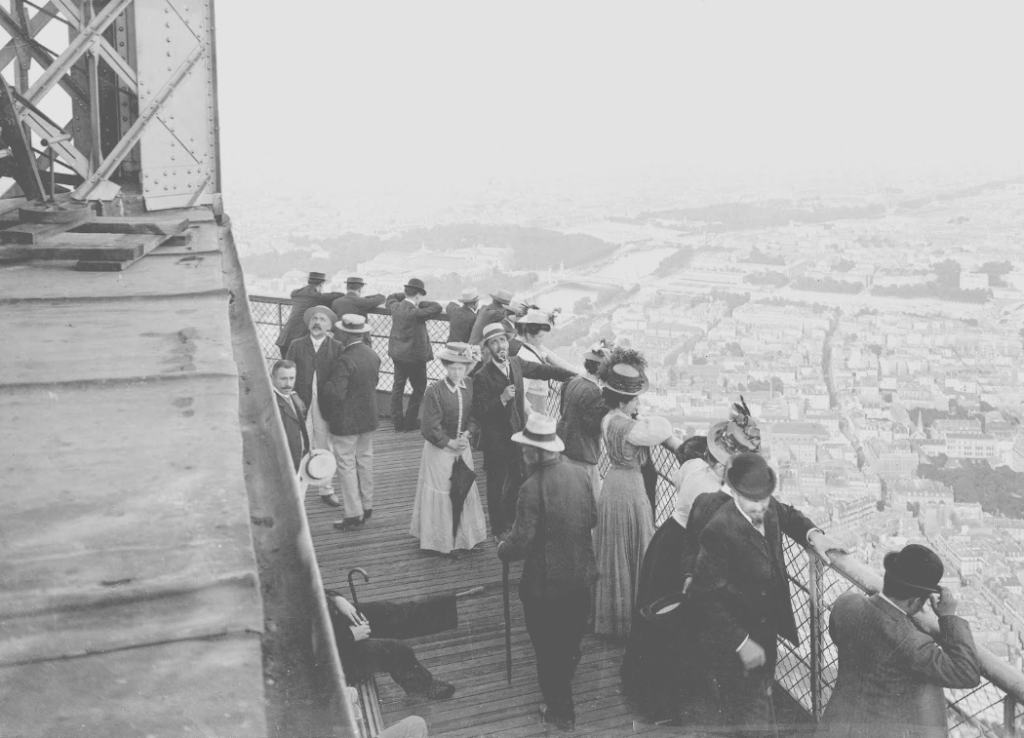

The construction proceeded at record pace—five months for foundations and twenty-one months for the metal assembly. Despite the predictions of aesthetic doom, public opinion shifted dramatically once the tower was completed. It received two million visitors during the 1889 World’s Fair alone.

Legacy of Iron and Vision

The tower achieved its initial goal of showcasing French engineering capability, standing as the world’s tallest structure until 1930. But its true legacy has far exceeded its original purpose. Eiffel, ever practical, found new uses for his creation: a meteorological station in 1890, a military telegraph station in 1903, and a laboratory for studying aerodynamics in 1909.

Today, the structure that was supposed to be temporary (it had a 20-year permit) has become permanent—a global icon receiving some seven million visitors annually. Its silhouette has become shorthand for Paris itself, and its construction remains a testament to the power of innovative engineering and artistic vision.

The tower embodies a crucial moment in architectural history—when engineering stepped out of the shadows to create its own aesthetic. Those workers “reaping lightning bolts in the clouds” weren’t just assembling iron; they were building a bridge between the industrial and the sublime, proving that technical achievement could create its own kind of beauty.

From its foundations in the Seine to its graceful tip, the Eiffel Tower represents what humans can achieve when they dare to think beyond conventional limits. It stands not just as a tourist attraction or a feat of engineering, but as proof that sometimes the most controversial ideas become the most cherished landmarks. As Eiffel predicted, there was indeed “in the colossal, a unique attraction and charm”—one that continues to captivate millions more than 130 years after those first rivets were hammered into place.

Additional Facts

Additional Facts

Building Facts

The Eiffel Tower used 7,300 tonnes of Iron, 60 tonnes of paint, and 2.5 million rivets. It’s total width on the ground is 82 feet. It has 5 elevators from the esplanade to second floor and then 2 double lifts from second floor to the top. The tower itself stands at 1083 feet tall and weighs 10,100 tons.

Time to build

Ground breaking began on the 26th of January in 1887, and 2 years, 2 months and 5 days later, on March 31st 1989 the Eiffel tower was finished. This was a record breaking time to build such a marvel of engineering of the time.

1889 Exposition Univerelle

The 1083 foot Eiffel tower was planned to mark the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution and was scheduled to open at the 1989 Paris Exposition.