HOW A DRESS REVEALED THE ILLUSION OF HOW WE SEE

In February 2015, a picture of a dress sparked an intense debate that lit up the internet. Was it blue and black? Or white and gold? No one could agree. Lines were drawn, sides were taken. Even celebrities weighed in on #TheDress seen round the world. It sparked the question, how can we see color? It’s how we perceive the color spectrum.

But the most fascinating implication was far more than a party trick about fickle perceptions. According to brain scientists, the dress vividly exposed that color itself does not actually exist outside of our minds.

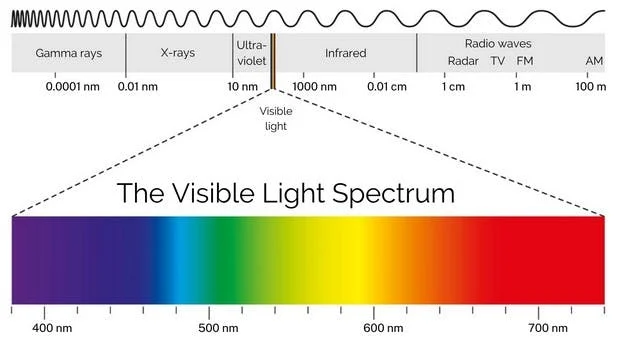

THE LIGHT SPECTRUM

To understand this concept, we must first explore what creates color at all. Essentially, color is the brain’s interpretation of various wavelengths along the light spectrum. Roy G. Biv helps remember the order – red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. This is the color spectrum.

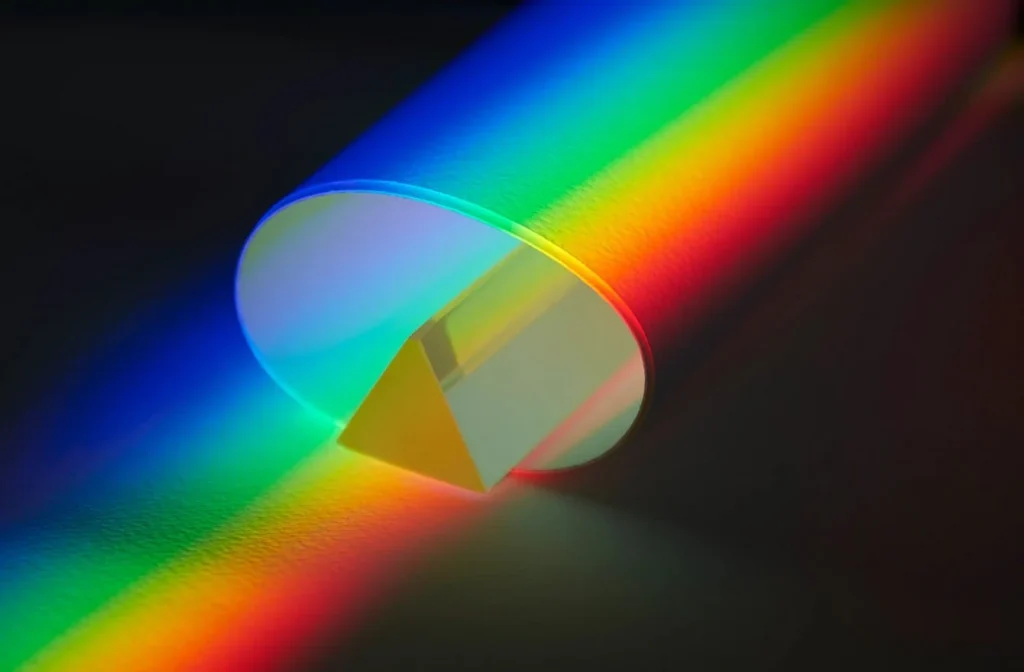

The wavelengths for violet are shorter and more energetic while red’s waves are longer and less so. When light hits an object, some wavelengths get absorbed while others bounce back to our eyes. The combo of waves entering the eye is what enables us to perceive color.

But there’s no inherent “blueness” or “redness” to the object itself. The atomic structure simply absorbs particular wavelengths that we eventually perceive as a color. Different distributions of waves trigger different color sensations in the brain.

SEEING ‘COLOR’

How can we see color? Well, the eyes and brain translate patterns of light into the experience of color spectrum. Special receptor cells called cones detect blue, red or green wavelengths. This input gets sent to the visual cortex as coded signals, which complexes neural networks then transform into color perceptions.

It’s why yellow and blue mix to form green in painting. Those hues contain light wavelengths that trigger both sets of cones in the eyes. The brain then combines those activations into the sensation we label “green.” But that experience happens solely in the mind, not inherent to any wavelength itself.

Even the context in which we view a color impacts how we perceive it thanks to this constructive process. “Color is this computation that our brains make that enables us to extract meaning from the world,” says neuroscientist Bevil Conway.

CULTURAL RELATIVITY

Perhaps the strongest proof that color is not objectively “real” is how differently cultures draw the lines between colors. The Himba tribe in Namibia, for instance, does not distinguish between blue and green the way English speakers do. Researchers found they actually have trouble telling those colors apart.

Russian speakers make more types of blue distinctions than English by separating lighter “goluboy” blue from darker “siniy.” What we simply label green is seen as a shade of blue in both Mandarin and Japanese. The color spectrum does not come pre-labeled for humans – we created categorizations for useful communication.

Even individual brains carve up colors differently, as the dress vividly demonstrated. The image was shot under uneven yellow lighting that created ambiguity. “It seems to be sitting at a stage where it’s bistable,” said neuroscientist Beau Lotto. About half of people discounted the dim lighting to see a white and gold dress. But the other half took the blueish tinge as the actual color.

PERCEIVING PERCEPTION

What made the dress go so wildly viral was how it forced us to confront the subjectivity of what we “see.” We assume we all perceive objective reality. But the jarring divide over this seemingly simple image highlighted that even basic sensations like color rely on complex internal construction.

In encountering someone who interprets the exact same input completely differently, we instantly grasp the inner workings creating our reality. “It’s seeing one reality, but knowing there’s another reality,” said Lotto. “So you’re becoming an observer of yourself.”

The dress vividly drove home that while light patterns physically exist outside us, the experience of color happens inside our skulls. This picture alone rattled those deeply rooted assumptions about objective sight.

Of course our eyes and visual cortex evolved to reconstruct reality accurately for survival needs. But the dress demonstrated that truth still takes a backseat to the overriding reality our brains generate moment to moment. Making sense of the world relies less upon what’s in front of us and more upon the perceptual magic behind our eyes.