Japan has a long fascination with eccentric game shows and reality TV concepts that often perplex Western audiences. But in the late 1990s, one show took this spectacle to alarming new height; “Susunu! Denpa Shonen”, highlighting serious ethical risks of exploitation in entertainment.

This shocking program subjected participants to extreme isolation and deprivation all while filming their suffering as comedy fodder for millions of viewers. The story of contestant Nasubi and his traumatic experience on the show reveals the darker side of reality television and the line between humor and inhumanity.

Outrageous Japanese Reality TV

Japanese game shows have mystified outsiders for decades with wacky premises like having people identify chocolate candies while blindfolded or get hit in the crotch when messing up tongue twisters. Shows like “Endurance” combined bizarre challenges like chugging hot sauce then immediately sniffing spicy mustard.

But some concepts went beyond just silly and verge into the realm of torture. “Troop of 100” had 100 people spontaneously chase an unsuspecting person on the street, leaving them rattled. “How to Escape a Fart” involved contestants spreading dyed gas around a room.

While these may have been ratings hits, a controversial new show emerged in 1998 that took things even further. “Susume! Denpa Shonen” subjected participants to demeaning, dangerous, and psychologically damaging situations all in the name of spectacle.

“Susunu! Denpa Shonen” Premise

Every season of “Susunu! Denpa Shonen” had a different survival-style concept aimed at attracting viewers through shocking hardships. Contestants had to hitchhike across Africa or escape a deserted island with no supplies.

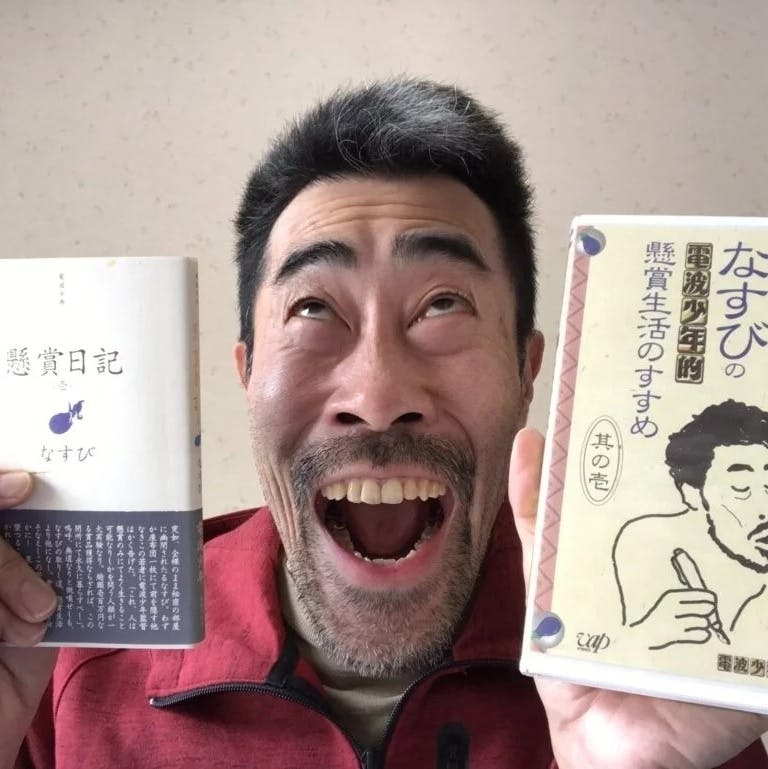

But one segment in particular drew the most attention – “Sweepstakes Life” featuring aspiring comedian Nasubi. The premise? Place Nasubi alone in an apartment with nothing but magazines. He had to survive only on prizes won by entering magazine sweepstakes until he reached $10,000 in winnings.

Producers stripped Nasubi naked and left him no clothes, food, or any outside contact. His real name was Tomoaki Hamatsu, but he was dubbed “Nasubi” as his genitals were covered by an animated eggplant for viewers, due to his nudity. This is also the origin of why the ‘eggplant’ emoji is now associated with the phallus.

For nearly a year, while supposedly entering over 1,400 sweepstakes a week, Nasubi starved in isolation as the camera filmed constantly. He believed he was self-recording footage that might air later. But in reality, his daily life was being broadcast nationally with mocking sound effects added.

At-Home Humiliation

As Nasubi slowly won meager prizes like dog food or rice to survive, the show depicted his progress – and emotional breakdowns – as comedy entertainment. He was denied any clothes besides lingerie, leaving him naked the entire time. Loneliness and starvation took an obvious toll as his speech slowed and he talked to inanimate objects.

Millions tuned in to watch the public exploitation and humiliation of Nasubi. In a country one-third the size, it broke ratings records at 17 million regular viewers. But as a foreign audience, most felt not amusement but moral revulsion. What could possibly be funny about human suffering manufactured for spectacle? Yet Japan was enthralled.

After 335 days surviving on his winnings, Nasubi finally reached the monetary goal. But producers cruelly moved him to an identical apartment in Korea, telling him to win enough to return home. Already traumatized, Nasubi suffered further before earning another ticket back.

When he arrived in Japan, Nasubi was again placed in a duplicate apartment and told to undress. Suddenly the walls collapsed – revealing a studio audience surrounding him. After 15 months isolated, this public spectacle pushed Nasubi to the brink. He was completely baffled as hosts explained millions had watched his degradation as entertainment for over a year.

Lasting Damage

Unsurprisingly, Nasubi exited the show scarred. He struggled holding conversations for months after being deprived of human contact. For a year, wearing clothes made him sweaty and uncomfortable. The hopeful comedian had become an unwilling reality star, left to handle the fame he never desired.

Yet when the show’s producer was confronted years later about Nasubi’s obvious trauma, he expressed no regret. He even disturbingly claimed it was “thrilling” to witness the “miracle” of human struggle recorded on film. Clearly no concern existed for contestants’ well-being.

But Nasubi has worked hard not to let those scars define him. In 2016, he climbed Mount Everest after several failed attempts, crediting the mental fortitude built through his harsh ordeal. And he continues performing comedy and acting today. Still, the show clearly extracted a heavy price.

The Appeal and Ethics of Reality TV Suffering

Nasubi’s experience poses uncomfortable questions about the line between entertainment and exploitation. Why do brutal reality shows attract such devotion? What drives the appeal of spectacles showcasing human pain?

Observers highlight voyeurism and the schadenfreude of enjoying others’ adversity. Watching people debased for amusement triggers our cruelest impulses. And Nasubi’s innocence in displaying unfiltered emotion – without realizing he was mocked by millions – made the show irresistible.

But as reality contests become more extreme, ethical concerns grow. Even shows like Survivor and Fear Factor profit off degradation. And subjects can suffer inhuman treatment yet have no power against the enterprise built around their suffering.

Many defend this as merely “fake” staging. But trauma still inflicts real damage, physically and mentally, regardless of context contrived for cameras. And fans are complicit in incentivizing intensifying brutality. Nasubi’s story illustrates the tipping point past which human dignity becomes expendable for ratings, putting superficial fun ahead of empathy.

Reality television will likely continue mining prurient impulses. But understanding what participants undergo for our idle entertainment is vital. Perhaps Nasubi’s unthinkable isolation and abuse can teach that no fleeting diversion justifies the long-term costs of manufactured human distress. The spectacle may entertain, but we must reconcile its inhumanity.

Additional Facts

Additional Facts

$2 Billion

The reality TV show ‘The Voice‘ has made over $2 Billion in ad revenue and has over 500 million viewers across the globe, making it the most watched Reality TV show.

34 Years

The reality show Cops has been on air since 1989, making it the longest running reality show on TV. It’s also one of the first ever reality shows to air on TV. With over a 1,000 episodes, yes, it’s still airing

33.35%

The Amazing Race was the most globally demanded reality TV show, with 33.35% demand share as of 2021.