For centuries, the phrase “burning of the Library of Alexandria” has conjured an image of mankind’s greatest collection of knowledge going up in flames. It’s become a metaphor for the triumph of ignorance over learning, a cautionary tale passed down through generations. From the French Revolution to the conflicts in the Balkans, the destruction of libraries and archives has been measured against this legendary loss. But the true story of what happened to humanity’s most ambitious attempt to gather all known knowledge under one roof is far more complex – and perhaps more relevant to our times – than the popular myth suggests.

But what, exactly, happened to the Library of Alexandria? The answer proves far more complex than the popular image of a great conflagration reducing centuries of knowledge to ash. The story of the library’s demise has become not just history, but mythology – a cautionary tale that continues to resonate in our own era of digital archives and endangered public libraries.

The Birth of a Knowledge Empire

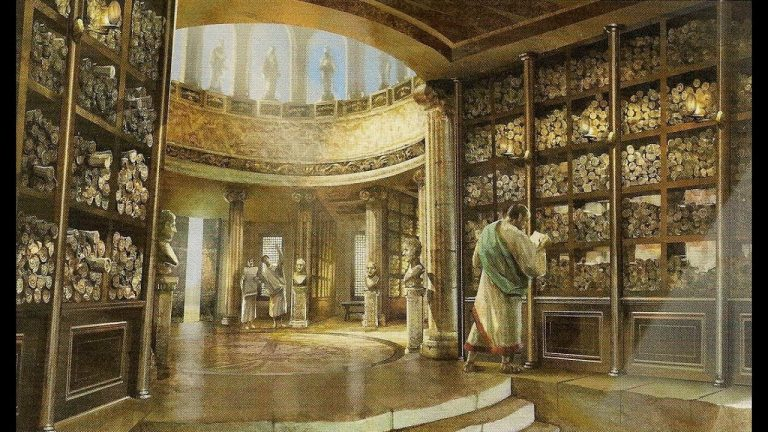

The story begins with ambition. In 283 BCE, Ptolemy I Soter, successor to Alexander the Great as Pharaoh of Egypt, founded an institution unprecedented in scope and ambition. The Museum (Mouseion, “Seat of the Muses”) was conceived as a universal center of learning, modeled after Aristotle’s Lyceum in Athens. This wasn’t just a collection of books – it was a complete research institution, featuring lecture halls, gardens, a zoo, and shrines to the nine muses. At its heart stood the library itself, ultimately housing what some estimates suggest were hundreds of thousands of scrolls from across the known world.

The institution actually comprised two main facilities: the main library within the Mouseion and a “daughter” library at the Temple of Serapis (the Serapeum). Over 100 scholars lived on-site, dedicating themselves to research, writing, lectures, and the painstaking work of document translation and reproduction. Every ship that docked in Alexandria was required to surrender its books for copying, a policy that helped build the collection’s legendary scope.

Multiple Stories of Destruction

The popular imagination has long clung to the image of a single catastrophic fire that erased this treasure trove of ancient knowledge. Yet historical records present us with multiple candidates for the library’s destroyer, each account colored by the biases and agendas of its time.

Julius Caesar stands as the first accused. In 48 BCE, while pursuing his rival Pompey into Egypt, Caesar found himself trapped in Alexandria by an enemy fleet. His tactical decision to burn the ships in the harbor sparked a fire that spread to nearby buildings. Caesar himself wrote of starting the harbor fire but conspicuously omitted any mention of damage to the library – an omission that later historians have debated extensively.

The story grows more complex in the Christian era. Around 391 CE, Patriarch Theophilus oversaw the conversion of the Serapeum into a Christian church. While some accounts suggest this led to the destruction of books, contemporary sources – even those hostile to Christianity – make no mention of a library being destroyed during this transformation.

Perhaps the most colorful account involves the Muslim Caliph Omar in 640 CE. According to this tale, when informed of the library’s existence, Omar supposedly declared its contents either contradicted the Koran (making them heretical) or agreed with it (making them superfluous) – either way, justifying their destruction. The scrolls allegedly fueled the city’s bathhouses for six months. However, this account wasn’t recorded until three centuries after the supposed event, by a Christian bishop known for his anti-Muslim writings. This account has also been debunked by many historians including Bernard Lewis who was known to be a vocal critic of Islam and coined the term ‘Clash of Civilizations.’

Beyond the Flames: A Different Story

While fires and destruction certainly played a role in the library’s history, modern scholars increasingly point to a less dramatic but perhaps more tragic explanation: gradual decline through neglect and the natural degradation of materials. Edward Gibbon, the great Enlightenment historian, dismissed the more sensational destruction narratives (some listed above) in favor of this interpretation.

The reality of ancient libraries was far more precarious than our modern institutions. Papyrus scrolls, the primary medium for texts, were inherently fragile. Without constant care and recopying, collections could literally crumble away. The decline of institutional support and changing priorities in later Roman Egypt likely contributed more to the library’s eventual disappearance than any single act of destruction.

The Hypatia Connection

No discussion of the Library of Alexandria would be complete without addressing Hypatia, the brilliant philosopher and mathematician often associated with the institution’s final days. Popular culture, including the 2009 film “Agora,” has often portrayed her murder by a Christian mob in 415 CE as inextricably linked with the library’s destruction. However, historical evidence suggests a more nuanced reality.

Hypatia’s death, while undoubtedly tragic, appears to have been primarily politically motivated rather than an attack on learning or the library itself. Moreover, recent scholarship indicates that the Great Library as an institution had likely ceased to exist in its original form long before Hypatia’s time, though smaller collections may have persisted.

Modern Resonance

The story of Alexandria continues to resonate powerfully in our own time. Today’s challenges to knowledge preservation take different forms but raise similar concerns. Public libraries face funding cuts, digital archives grapple with format obsolescence, and the concentration of information in the hands of a few large technology companies raises questions about access and control.

In 2002, these concerns helped inspire the creation of the new Bibliotheca Alexandrina in modern Alexandria. This institution, with its vast server farms humming where ancient scholars once studied papyrus scrolls, represents both a connection to the past and a commitment to future knowledge preservation.

The library’s digital focus highlights a crucial modern challenge: while we can store more information than the ancient Alexandrians could have imagined, digital preservation comes with its own vulnerabilities. Format changes, hardware deterioration, and the need for constant maintenance echo the challenges faced by ancient librarians protecting their papyrus scrolls.

Lessons from Alexandria

The true story of the Library of Alexandria – one of gradual decline rather than dramatic destruction – offers perhaps more relevant lessons for our time than the popular myth of a great conflagration. It reminds us that the preservation of knowledge requires constant vigilance and support. The greatest threats often come not from dramatic acts of destruction but from the slow erosion of commitment to maintaining and protecting our cultural heritage.

As Jacques Derrida observed, “There is no political power without power over the archive.” The control and preservation of knowledge remains as politically relevant today as it was in ancient Alexandria. Whether through war, neglect, or the shifting priorities of societies, the loss of knowledge institutions carries profound consequences for human civilization.

In 1980, Carl Sagan captured this enduring significance when he told his television viewers that if he could travel back in time, he would choose to visit the Library of Alexandria. “All the knowledge in the ancient world was within those marble walls,” he said, his voice carrying both wonder and warning. For Sagan, the library’s fate carried a message across sixteen centuries: “we must never let it happen again.”

This warning resonates differently today than Sagan might have imagined. The threat to our knowledge institutions may not come from dramatic acts of destruction but from something far more insidious: the gradual erosion of support for the institutions that preserve and share human knowledge. Whether through marble halls or digital archives, the dream of preserving and sharing human knowledge across generations continues to inspire and challenge us. The true lesson of Alexandria may be that civilization’s memory requires not just protection from catastrophe but sustained commitment to its preservation.