This Content Is Only For Subscribers

Introduction

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a dark chapter in American history unfolded. Cities across the United States enacted “ugly laws,” targeting and discriminating against people with disabilities. These laws, rooted in prejudice and misconception, banned individuals deemed “unsightly” from public spaces. The story of the ugly laws is one of cruelty, marginalization, and the long fight for equality.

The Birth of the Ugly Law: San Francisco, 1867

San Francisco, a city shaped by the Gold Rush and Civil War, became the birthplace of the first ugly law in 1867. The city’s Board of Supervisors passed Order No. 873, prohibiting “street begging” and restricting “certain persons from appearing in streets or public places.” The law targeted those considered “diseased, maimed, mutilated or in any way deformed.”

Disabled veterans and struggling immigrants filled San Francisco’s post-war landscape, all trying to make ends meet. Instead of empathy, they faced hostility. Newspapers labeled them “lazzaroni,” “objects of horror,” and “hideous monstrosities.” The ugly law became a tool to remove the “unsightly” from public view.

Enforcing the Law: Incarceration and Almshouses

San Francisco’s ugly law led to the incarceration of disabled individuals. Some were sent to jail, while others were confined to the massive almshouse, later known as Laguna Honda Hospital. The only crime committed by many was being a disabled person in public.

The almshouse became a dumping ground for the “inmates,” mostly elderly and physically unable to work. By 1892, the almshouse confined nearly 800 people, with the ugly law stripping away their freedom by deeming them unfit for society.

The Spread of the Ugly Laws

As the 19th century progressed, ugly laws modeled after San Francisco’s spread like wildfire. Major cities and communities along railroad lines adopted these discriminatory ordinances. The 1890s, marked by a severe depression, saw an even greater proliferation of ugly laws.

The implementation of these laws was heartbreaking. In 1916, Portland, Oregon, paid a woman named Mother Hastings to leave the city because she was “too terrible a sight for the children to see.” She took the money and moved to Los Angeles, her dignity stripped away by a cruel and unjust system.

The Intersection of Disability and Economic Status

While ugly laws ostensibly targeted people with disabilities, the reality was more complex. The laws were primarily enforced against those who were unemployed and receiving public assistance. Disability alone did not make one a target; it was the intersection of disability and economic status that drew the ire of the law.

Employers in the 19th century did not necessarily view disability as a disqualifier for work. Employers often viewed a missing finger as a sign of experience, since industrial accidents happened frequently. The public generally considered Civil War veterans with disabilities worthy of aid, and these veterans eventually won a federal pension benefit.

The real targets of the ugly laws were the “unworthy poor,” lumped together with “lazy” and “profligate” individuals in the eyes of the law. The ugly laws were a manifestation of society’s prejudices against those who did not fit the mold of the self-sufficient, able-bodied worker.

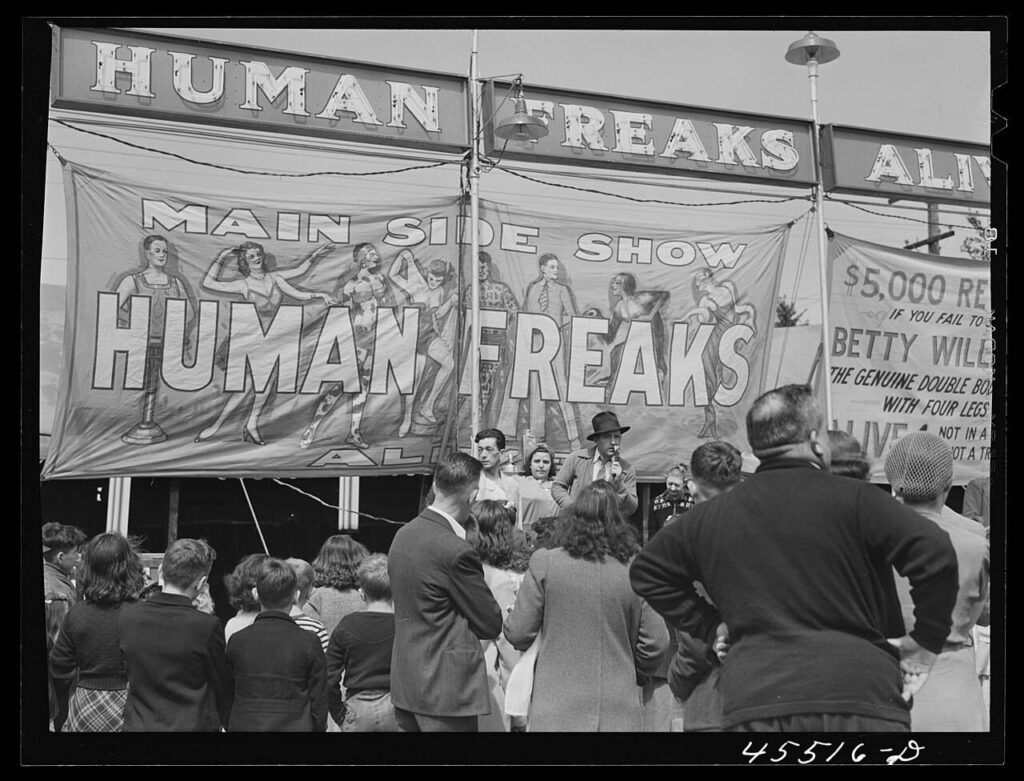

The Contrast of Freak Shows

In a stark contrast to the ugly laws, freak shows featuring individuals with disabilities were popular forms of entertainment in the late 19th century. The same year Chicago passed its ugly law, the city government permitted the “exhibition of monsters or freaks of nature.”

When Illinois attempted to ban freak shows in 1899, the law was overturned within a year. The reasoning? It prevented the shows and the “freaks” themselves from earning money. The irony was glaring: disabled individuals could be put on display for profit but were banned from freely existing in public spaces.

The Long Road to Repeal

The ugly laws remained on the books well into the 20th century. Enforcement slowly waned, particularly after World War I, when discriminating against veterans became politically unpalatable. However, the last known case of an ugly law arrest occurred in Omaha in 1974.

When the case reached the courts, a judge asked, “What’s the standard of ugliness? Does the law mean that every time my neighbor’s funny-looking kids ask for something I should have them arrested?” The city prosecutor declined to press charges, and the era of ugly law arrests came to an end.

The Fight for Disability Rights

The history of the ugly laws is just one chapter in the long fight for disability rights in the United States. The 20th century saw gradual progress, from the Smith-Fess Act of 1920, which provided vocational assistance to Americans with physical disabilities, to the Social Security Act of 1935, which offered benefits for the blind and physically disabled.

In 1973, the Rehabilitation Act prohibited discrimination based on disability in programs funded by federal agencies. The 504 Sit-In of 1977 was a pivotal moment, with disability rights activists occupying federal buildings to demand the signing of regulations to enforce the Rehabilitation Act.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 marked a significant milestone, providing comprehensive civil rights protections for individuals with disabilities. The ADA was the culmination of decades of activism and advocacy, led by organizations like American Disabled for Attendant Programs (ADAPT) and countless individuals fighting for their rights.

Conclusion

The history of the ugly laws is a sobering reminder of the prejudice and discrimination faced by people with disabilities in the United States. These laws, born out of ignorance and cruelty, subjected individuals to incarceration, marginalization, and the stripping away of their basic human dignity.

But the story of the ugly laws is also one of resilience, activism, and the tireless pursuit of equality. From the 504 Sit-In to the passage of the ADA, disability rights activists fought to dismantle the systemic barriers and discrimination that had long plagued their community.

As we reflect on this dark chapter in American history, we must acknowledge the progress made and the work that still lies ahead. The legacy of the ugly laws serves as a reminder of the importance of inclusivity, empathy, and the recognition of the inherent worth and rights of every individual, regardless of their abilities.

In a society that truly values equality, there is no place for laws that discriminate and marginalize. The story of the ugly laws and the fight for disability rights is one that must be told, remembered, and used as a catalyst for continued progress. It is a story of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity and a call to action for a more just and inclusive world.

FAQ: Common Questions About California’s Ugly Law

When was the first ugly law passed? July 9, 1867, in San Francisco (Order 783).

Who was Martin Oates? A disabled Union veteran jailed in 1867 for violating Order 783, the first known ugly-law arrest.

Did Los Angeles have an ugly law? It proposed one in 1913, but public backlash killed the measure.

When were ugly laws repealed? Most quietly vanished in the 1960s-70s; Chicago removed the last in 1974.

How do ugly laws influence policy today? Scholars link them to modern sit/lie and anti-camping ordinances targeting homelessness.

San Francisco’s ugly law reminds us how easily prejudice can become policy. The ordinance that criminalized Martin Oates and countless others represents an uncomfortable truth about our past—and challenges us to recognize similar patterns of exclusion in the present. Understanding this history helps us work toward truly inclusive public spaces where no one faces arrest simply for existing.