This Content Is Only For Subscribers

The Genius of Einstein

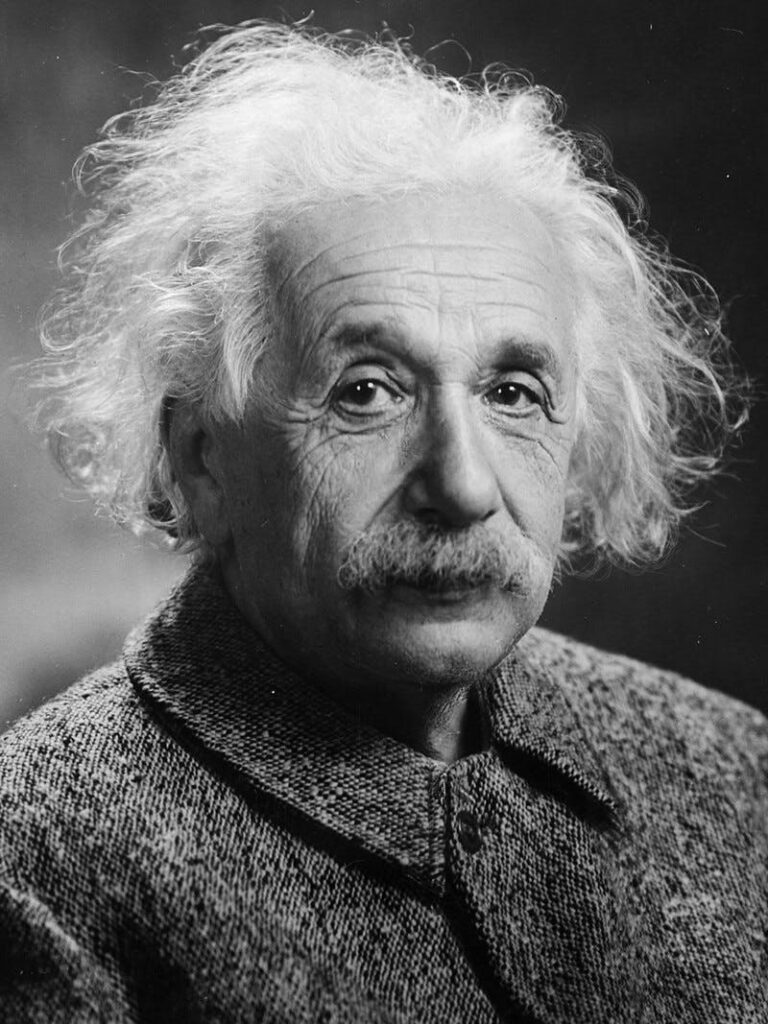

Albert Einstein is undoubtedly one of the greatest scientific minds in history. The German-born physicist developed the theory of relativity, which revolutionized our understanding of time, space, gravity, and the universe. His famous equation E=mc2 demonstrated the equivalence of mass and energy and laid the foundation for nuclear power. Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the photoelectric effect.

Beyond his scientific brilliance, Einstein was known for his pacifism, liberal politics, and advocacy for a Jewish homeland. His daring escape from Nazi Germany to the United States made him an international celebrity. Einstein was regularly consulted on ethical and political issues and rubbed shoulders with the likes of Charlie Chaplin. His tousled appearance and charming personality added to his icon status. There’s no doubt Einstein’s intellectual gifts made him a genius of the 20th century.

The Death of a Legend

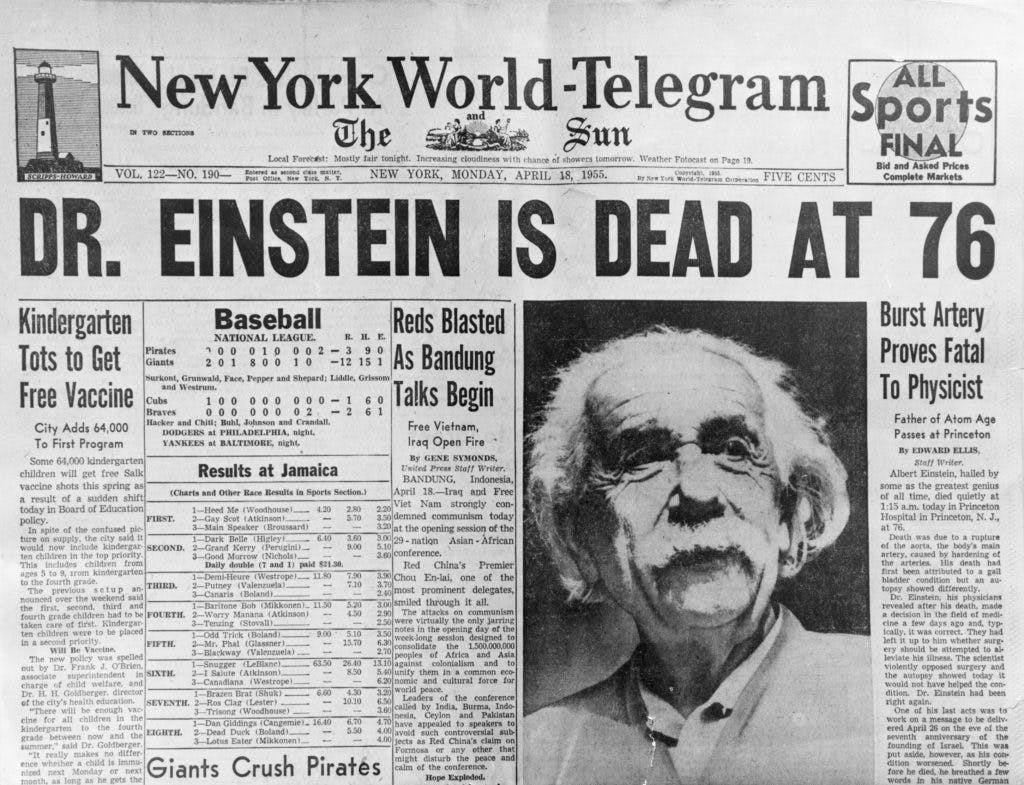

On April 18, 1955, Einstein experienced severe pain from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. At the Princeton Hospital, the 76-year-old refused invasive surgery, saying “It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go.” Later that day, the world-renowned scientist passed away peacefully in the hospital with his colleagues by his side.

Einstein did not want a funeral or for his body to be worshipped. He left instructions to be cremated and have his ashes scattered secretly. But Dr. Thomas Harvey, the pathologist who performed the autopsy, had other plans.

The Theft of a Celebrated Mind

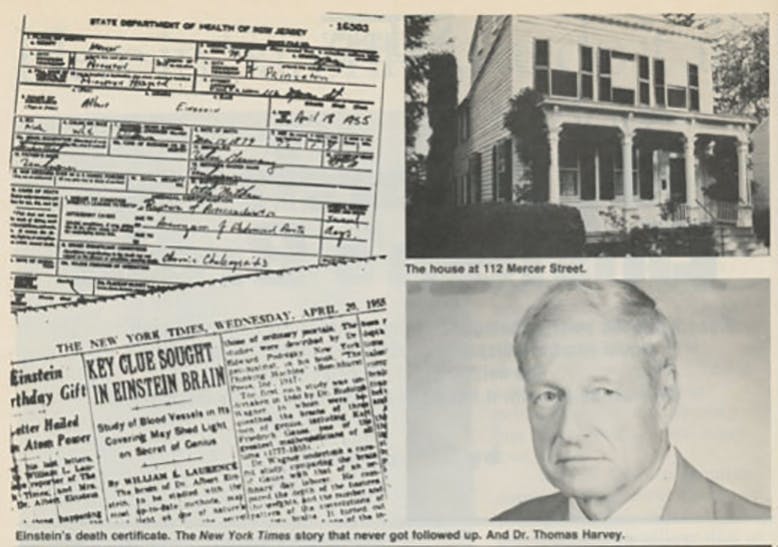

Against Einstein’s wishes, Dr. Harvey decided to preserve the physicist’s brain for scientific study. He removed the organ and kept it without initial permission from Einstein’s family. Harvey photographed and dissected the brain into over 200 pieces, hoping to gain insight into Einstein’s genius. Harvey reflected, “I knew we had permission to do an autopsy, and I assumed that we were going to study the brain.”

Unfortunately, this assumption would cost Harvey his job. The removal was front page news the next day, generating headlines like “Doctor Takes Einstein’s Brain.” As neither Einstein nor his family had consented to the unusual act, Harvey faced serious repercussions. He was dismissed from Princeton Hospital on grounds that he had violated the autopsy protocol.

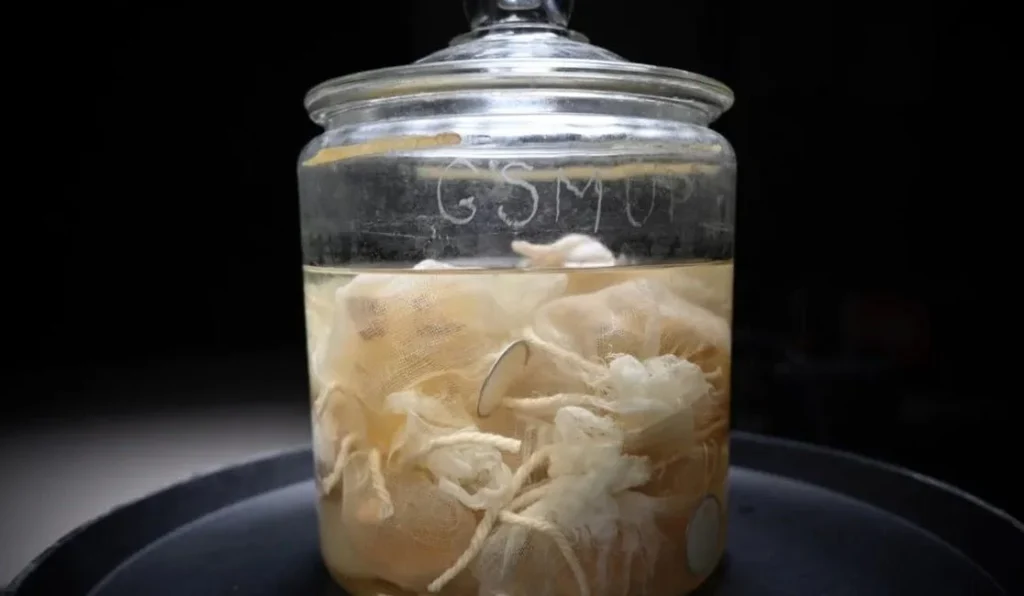

Harvey was determined to continue studying the brain, believing the anatomy held the key to Einstein’s intellect. So he kept the dissected remains, which he had preserved in celloidin, a rubbery type of cellulose. Harvey placed the pieces of Einstein’s brain into two glass jars and relocated to Philadelphia. This time, he had permission from Einstein’s son Hans Albert, provided that any investigation was only conducted for scientific purposes. But Harvey would soon find studying the historic brain in his basement was easier said than done.

The Hidden Brain

Over the next four decades, Thomas Harvey struggled to find researchers interested in examining Einstein’s brain. As he lacked expertise in neuroscience himself, Harvey needed to partner with the right scientists to gain insight from the organ. But the pathologist found it difficult to convince specialists of the value in analyzing a single brain without comparisons.

There were also few legal options at the time for obtaining control brains for comparison. Additionally, Harvey’s conduct had been publicly scrutinized, making many in the research community wary. As interest and funding failed to materialize, Harvey’s treasured specimen remained mostly confined to storage.

Between New Jersey, Missouri, Kansas, and back again, Harvey transported Einstein’s brain bits in nondescript containers, tucked away from the public eye. At one point, his wife threatened to dispose of the bothersome brain pieces. For decades, the historic organ stayed stowed away in basements, hidden in beer coolers and cider boxes, as Harvey struggled to unlock its secrets.

Questionable Science

Finally, in the 1980s, over 30 years after Einstein’s death, Thomas Harvey partnered with scientists willing to study the preserved cerebral matter. His first collaborators were researchers at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1985, the team published the first examination of Einstein’s brain in the journal Experimental Neurology.

Using celloidin-embedded slide samples Harvey provided, the authors claimed Einstein’s brain had an abnormally low neuron-to-glia ratio in the region known as Brodmann area 39. Glia are cells that support and protect neurons. The researchers speculated this distinctive cellular makeup might explain Einstein’s mathematical and spatial skills. However, the small control sample of 11 brains and lack of blinded cell counting raised considerable criticism.

More questionable studies soon followed. Harvey joined with Alabama scientists to count neurons in Einstein’s frontal cortex from digitized photos, declaring the region was thinner than average. Canadian researchers also obtained photos of Einstein’s brain that Harvey had collected prior to dissection. Comparing surface features, that team conjectured Einstein’s unusual parietal lobe anatomy could underlie his mathematical talents.

But all these studies were fundamentally flawed. They relied on tiny samples of the brain, inappropriate control groups, and measurements that were not blinded. The researchers frequently lacked expertise in pathology and made unsupported leaps between anatomy and intelligence. Overall, the science behind Einstein’s stolen brain failed to deliver conclusive insights.

Controversial Samples

Seeking to further investigate Einstein’s neurobiology, Harvey divided up portions of the brain to mail off to researchers across the globe. He hoped disseminating samples would help achieve his dream of learning what made Einstein tick. In addition to sending slices to Berkeley, Harvey parceled out bits of cerebrum to specialists in Toronto, New York, and even Japan.

However, not all recipients handled the samples ethically. One of the Japanese researchers kept the rare chunk of Einstein’s brain he was loaned rather than returning it. The brain portions mailed overseas became subject to legal disputes over rightful ownership. Harvey himself even came under investigation for transporting the specimens outside the U.S. without proper documents.

Sharing samples internationally enabled more scientists to probe the mysteries of Einstein’s mind. But it came at an ethical cost and yielded controversial results. Studies on the brain chunks showed a range of alleged anomalies – more compact neurons, thicker cortex, expanded glial cells. Yet issues with tiny samples and lack of blinded controls persisted. The investigations sparked debates about interpreting brain anatomy without an owner’s permission. In the end, the fantastical research failed to definitively reveal correlates of Einstein’s aptitude.

The Failures of Phrenology

Why did decades of microscopic analyses on Albert Einstein’s stolen brain fail to illuminate the source of his imaginative genius? As it turns out, reducing the seat of a man’s intellect to bits of flesh in jars is an endeavor doomed to futility. Einstein himself warned: “not everything that counts can be counted.”

The pseudo-scientific studies on Einstein’s brain hark back to the days of phrenology. This antiquated theory claimed that localized brain regions controlled specific talents like language, logic, or music. Phrenologists read head bumps to decipher mental strengths. But modern neuroscience reveals that human cognition arises from distributed neural networks, not particular areas.

Of course, there are singularities to Einstein’s life experience that shaped his breakthroughs. His personality, upbringing, encounters with nature, and education formed meaningful patterns within his brain. But these connections can’t be gleaned from slivers of dead cells. In the end, the crude grave robbery and dissection of Einstein’s brain failed to capture the ineffable spark of genius it once cradled. The ill-begotten samples served only as a potent reminder that our minds transcend mere matter.

The Afterlife of a Brilliant Organ

What became of Einstein’s brain after this frenzied period of misguided research? In the 1990s, Thomas Harvey returned the remainder of the brain to Princeton Hospital. A pathologist named Elliott Krauss took over stewardship, promising to protect the organ’s dignity. Most of the brain pieces were preserved in formaldehyde, while Einstein’s eyes stayed in a safe deposit box.

When Krauss died in 2007, he passed the baton to another pathologist, Michael Paterniti. Einstein’s brain pieces were relocated to Paterniti’s lab in New Jersey. Photos leaked in 2010, showing crinkled grey matter in old glass jars. Scientifically useless but historically precious, the specimens remain sequestered from public view.

The saga of Einstein’s purloined brain underscores how even men of conscience can rationalize questionable acts in hopes of advancing knowledge. Yet the folly of Harvey’s endeavor proves the limitations of reducing genius to biology. Einstein’s true legacy lives on not through remnants of his anatomy, but through the boundless creativity he unleashed in life. As Einstein mused, “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.” His greatest ideas echo through spacetime not because of brain matter, but the metaphysical matter of his mind.

Additional Facts

Additional Facts

26 Years old

Einstein was only 26 when in his miracle year of 1905 he published 4 papers that gave birth to the foundation of Modern Physics. This included publishing the famous E=Mc² equation and the paper on the Photoelectric Effect that won him the Nobel prize in 1921

“Much too fat”

When Einstein’s grandmother first saw him as a baby, she exclaimed “Much too fat, much too fat!”

A compass

When Einstein was 5 years old his father gave him a compass. This child was fascinated by the fact that the needle always pointed one direction, giving him insight that there are forces that drove the Universe that we can’t see, sparking his interest in Science.