The Last Witness: Samuel J. Seymour’s Unforgettable Account of Lincoln’s Assassination

On a fateful night in 1865, a young boy of just five years old witnessed one of the most pivotal events in American history – President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Samuel J. Seymour, who would later recount his experience on the 1956 episode of the TV show “I’ve Got A Secret,” remains the last living witness to this tragic event. Now, over a century later, we delve into Seymour’s riveting account and explore the emotions and vivid details of that unforgettable night.

A Young Boy’s Fateful Trip to Washington, D.C.

Samuel Seymour’s first trip away from home was not one he would ever forget. Accompanied by his father on a business trip to Washington, D.C., the young boy was frightened by the sight of soldiers and guns lining the streets. To help calm his nerves, Seymour’s nurse, Sarah Cook, and his godmother, Mrs. Goldsborough, decided to take him to a play at Ford’s Theater. Little did they know, this was to be a night that would change the course of history.

The Calm Before the Storm: Settling into Ford’s Theater

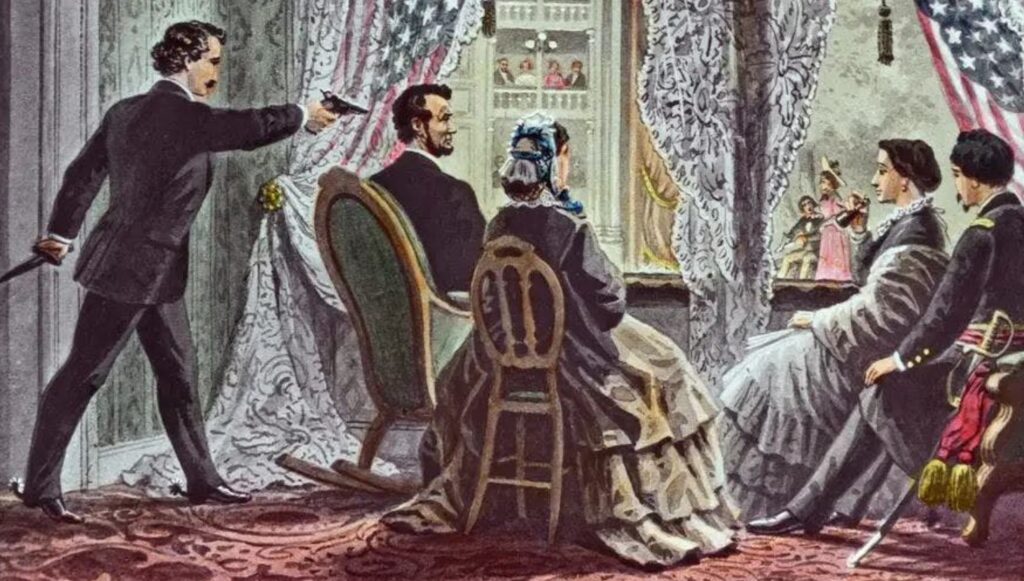

As the trio settled into their balcony seats across from the presidential box, Seymour’s godmother pointed out the colorful flags adorning the box where President Lincoln would be seated. When the tall, whiskered figure of the President finally arrived, he smiled and waved to the audience. This gesture temporarily lifted the somber mood in the theater. As the play, “Our American Cousin,” progressed, young Seymour’s anxiety gradually eased.

The Calm Before the Storm: Settling into Ford’s Theater

Suddenly, a shot rang out, and the theater was plunged into chaos. In an interview with Frances Spatz Leighton, Seymour described the scene: “All of a sudden a shot rang out – a shot that always will be remembered – and someone in the President’s box screamed. I saw Lincoln slumped forward in his seat.” Unbeknownst to the young boy, the shot he had heard was fired by John Wilkes Booth. Booth had chosen the play’s funniest line to mask the sound of his single-shot derringer.

Chaos and Confusion: A Child’s Perspective on Tragedy

Confusion and panic swept through the theater, with many audience members unsure of what had transpired. Seymour, too, was bewildered by the turn of events. “I thought there’d been another accident when one man seemed to tumble over the balcony rail and land on the stage,” he recalled. Seymour’s innocence and compassion shone through as he urged his nurse and godmother to help the man who had fallen. This man was none other than Booth himself, who had injured his leg in the jump.

As pandemonium erupted, cries of “Lincoln’s shot! The President’s dead!” rang through the air. Mrs. Goldsborough scooped up the young boy and whisked him out of the theater. In his retelling of the event, Seymour revealed that the horror of that night would haunt his dreams for years to come. “That night I was shot 50 times, at least, in my dreams – and I sometimes still relive the horror of Lincoln’s assassination, dozing in my rocker as an old codger like me is bound to do,” he said.

Seymour’s Account: A Unique Perspective on History

Seymour’s account of the assassination, published in the February 7, 1954 issue of The American Weekly, provides a unique and heart-wrenching perspective on the event. There are more detailed recollections of the event from Major Henry Rathbone and others present at Ford’s Theater that night. However, Seymour’s childlike innocence and naivete offer a touching and humanizing contrast into a tragic moment in American history.

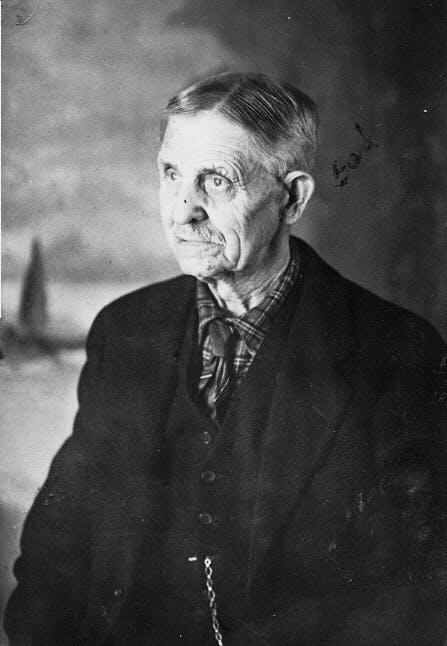

The story of Samuel Seymour resurfaced decades later when he appeared on the CBS TV panel show “I’ve Got a Secret” on February 9, 1956. Despite suffering a fall prior to the show that left him with a swollen knot above his right eye, Seymour insisted on sharing his story with the nation. Host Garry Moore and the show’s producers had urged him to forgo his appearance. However, the resilient witness was determined to recount his experience. Panelists Bill Cullen, Jayne Meadows, and others questioned Seymour. They pieced together his secret connection to the Civil War and the political significance of his story. And in the end, finally, his eyewitness account of Lincoln’s assassination.

A Humble Man’s Legacy

Seymour’s appearance on the show provided a rare opportunity for the American public to hear a firsthand account of Lincoln’s assassination from the last living witness. In an era when television was still a relatively new medium, viewers were captivated by the old man’s tale. He painted a vivid picture of that fateful night in 1865. As a testament to his humility, Seymour received a can of Prince Albert pipe tobacco from the show’s sponsor, R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, in lieu of the usual prize of a carton of Winston cigarettes.

Samuel J. Seymour passed away on April 12, 1956, at his daughter’s house in Arlington, Virginia. He left behind a legacy of five children, thirteen grandchildren, and 35 great-grandchildren. Today, Seymour rests in Loudoun Park Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland. His story however, lives on through the accounts he shared in print and on television.

The Power of Storytelling: Transporting Us Back to That Fateful Night

Seymour’s poignant and vivid description of Lincoln’s assassination stands as a testament to the power of storytelling. It captures the emotion and turmoil of a moment that forever changed the United States. Through his words, we are transported back to that fateful night in Ford’s Theater, experiencing the fear, confusion, and heartbreak of a nation in mourning. Moreover, Seymour’s account serves as a reminder of the resilience of the human spirit. It also shows the compassion and innocence of a young boy who, despite witnessing a tragedy beyond his comprehension, sought to help a fellow human in need.

“I saw John Wilkes Booth shoot Abraham Lincoln (April 14, 1865).”

Samuel J. Seymour