EARLY RECORDING TECHNOLOGY PROPELLS BLACK MUSIC TO MASS AUDIENCES

Long before hip hop and rock ruled the airwaves, jazz and blues innovators battled racial barriers to harness the power of radio and records – birthing pop music’s rise. This is the story of the origin of Jazz. Their drive to share African American sounds with the world sparked artistic movements still resonating globally. This is the story of genres crossing over from subculture to popular sensation through the defiant efforts of musical pioneers.

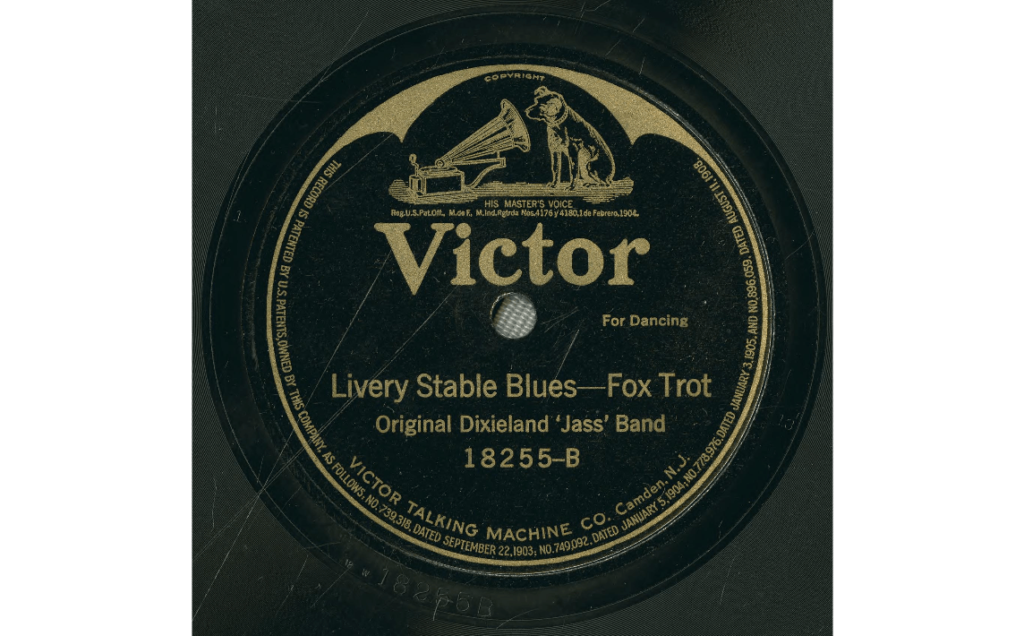

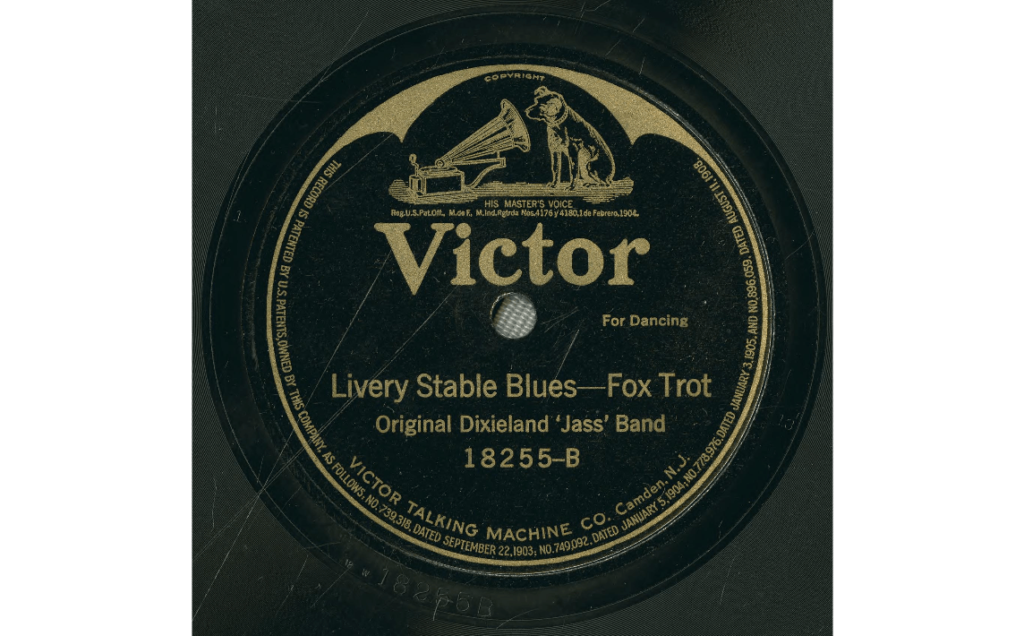

Notice the genre is listed as Fox Trot.

JAZZ JOLTS THE SCENE

Our journey starts around 1917 when seismic rhythmic ripples from New Orleans washed ashore in American living rooms. That February, the Victor label released the very first jazz recording – “Livery Stable Blues” by the all-white Original Dixieland Jazz Band. While not technically the creators, they rode jazz’s building momentum.

For context, blues had emerged years earlier as informal songs from Southern black communities. Artists bent notes outside traditional scales while channeling longing and heartache into vocal laments. Mostly performed privately, niche labels selling “race records” began circulating early blues to African American consumers.

Then around the turn of the century, virtuoso pianist Jelly Roll Morton and other New Orleans artists started blending ragtime’s syncopation with blues’ grittier tones. The result was an exciting new hybrid dubbed “jazz.” Due to segregation, white audiences initially encountered jazz via traveling vaudeville shows instead of through early black innovators like Morton.

But recording technology unlocking music’s mass reach would change everything.

PUSHING PAST BARRIERS

As jazz captured young imaginations, white bands helped popularize the sound since big labels refused to market black artists to white audiences back then. But bold African American composers like W.C. Handy strategized getting influential white singers to cover his hits.

Handy’s 1914 tune “Memphis Blues” skyrocketed from charming white concert-goers to the recording studios pressing discs for eager fans. Publishers now scrambled to release jazz sheet music as piano sales boomed nationwide.

Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake dodged theatrical racism to perform snappy numbers in fine suits instead of the degrading minstrel show blackface. Their music enthralled integrated crowds – foreshadowing wider acceptance ahead.

Beyond lingering minstrel caricatures in artwork, African American songwriters still confronted barriers preserving creative autonomy. Crafty tactics like narrative songs shaming record executives helped protest the prejudice hampering jazz’s crossover appeal.

CAPTIVATING A NATION

As the 1920s roared in, New York’s thriving nightlife kindled jazz’s spread from Southern speakeasies to Chicago ballrooms. Captivating dancers with intoxicating rhythms and loose improvisation, hot jazz symbolized a sexy radical rebellion against convention – the birth cries of cool.

Though formulaic pop continued targeting mainstream fans, jazz’s grittier tones resonated across groups drawn to outlet and change during Prohibition-era frustration. The Harlem Renaissance also fostered jazz appreciation through intellectually elevating African American culture with literature, essays and political activism.

Suddenly jazz soundtracked the aspirational pulse of an increasingly modern, urban society. Its surging popularity exposed many whites, even curious European tourists, to black artists fueling phenomenal music innovation. By the 1930s, leading big bands jazzed up radio signals coast-to-coast, their swinging grooves now considered quintessentially American.

From backwater Southern juke to national sensation, early jazz pioneers had defiantly overcame racist hurdles to ignite pop’s first musical revolution. Now through mass media’s expansion, their ever-evolving art form floated abroad, its seeds planting global genres still flourishing today. Yet at home, rock and roll soon shook up the musical landscape once more.

ROCK REBELS UP THE ANTE

As post-war teenage culture hungered for rebellion symbols, jazz’s cool rebel edge gradually gave way to rock and roll’s grittier distortion mid-century. New technology like electric guitars, amps and 45 RPM records captured fiery rhythms inspiring defiant dances.

Mirroring civil rights momentum, early rock and roll also advanced black music integration. In 1951, Cleveland DJ Alan Freed coined the term “rock and roll” becoming among first white presenters showcasing R&B artists for mixed young crowds. Despite Jim Crow persisting, American Bandstand’s national broadcast beamed black rockers into white homes by 1957.

Still underrecognized as architects, 1950s black musicians pennedchart-toppers later repopularized by Elvis Presley, Pat Booneand other white acts with greater commercial access. Yet the musical fusion prevailed. By transporting marginalized sounds into the pop mainstream, rock and roll furthered innovative black music, paving lanes for hip hop and modern genres to follow.

FROM BLUES TO BLING

Over a century has passed since blues pioneers bent notes speaking to the weary soul. How astonishing that their marginalized melodies now underscore global voices through hip hop’s poetic anthems.

Like jazz and rock before it, hip hop incubated within disempowered communities before the irresistible beats launched block parties worldwide. Public Enemy’s biting lyrics, N.W.A.’s grit and Queen Latifah’s feminist bars expanded conception of black identity within popular culture. Soon rap lifted urban narratives from poverty’s periphery into household familiarity.

As music technology has globalized access once restricted along racial lines, modern black artists continue redefining pop’s boundaries. House music’s pulsating tempos still electrify dance floors. Nu-soul voyagers channel righteous ancestors while fusing afro-futuristic looks. Representation practically unknown pre-WWII now diversifies every stage and streaming playlist.

From blues innovators barred from shops stocking their records to present-day laureates like Kendrick Lamar, genre-blurring black musicians have relentlessly spearheaded pop’s progression through barriers. May their creative spark always Kindle revolutions still to come.