A Starry Morning in Oxford

In 1930’s Oxford, breakfast conversations between grandparents and their grandchildren weren’t usually front-page news. But for Venetia Burney, a bright-eyed student, one such conversation would etch her name in history by becoming the young girl who named Pluto. This young girl, residing amidst the cobblestone streets and towering spires of Oxford, was about to play a key role in the narrative of the universe.

The topic of the day? A newfound celestial body, a mysterious object located even beyond the distant Neptune.

An Eager Question

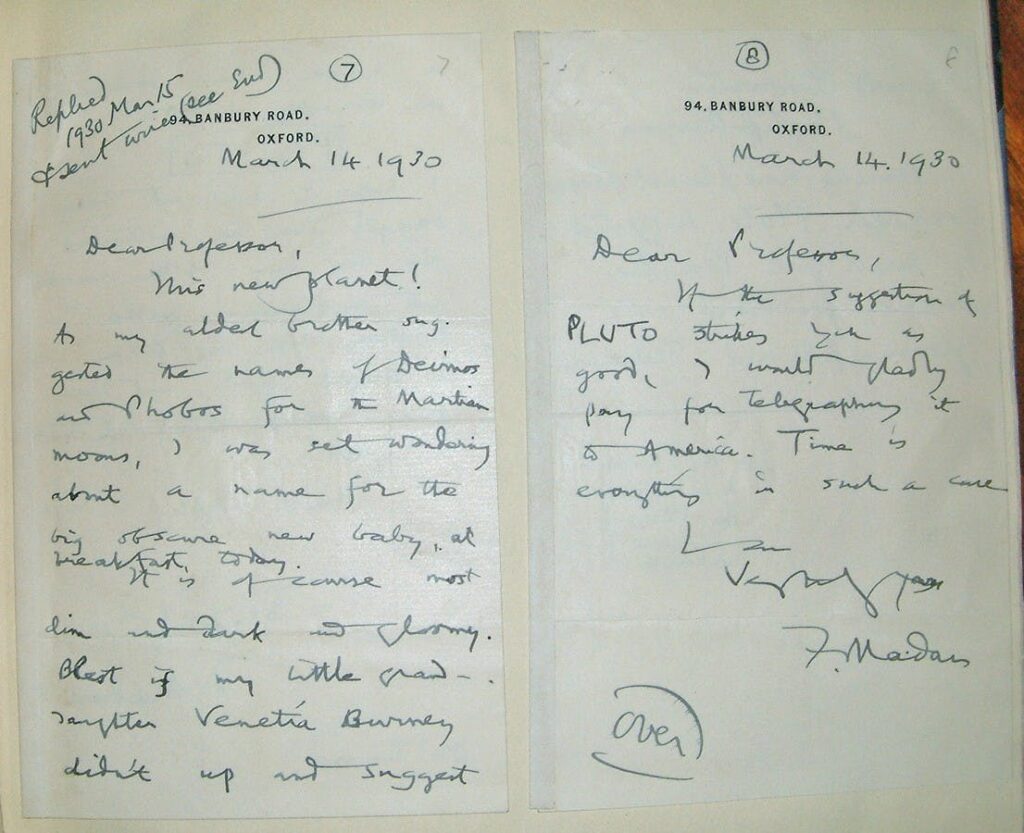

As Venetia and her family chewed over the details, the most significant question emerged: “What to name this new discovery?” This wasn’t just a routine discovery; it was a game-changer, reshaping our understanding of our own solar system.

Venetia, with her school-fueled knowledge of Greek and Roman mythology, let her imagination roam. Connecting the cool, remote characteristics of the new planet to the mythological underworld, she posed a simple, yet profound suggestion: “What about Pluto?”

This is the moment in history when Venetia became the young girl who named Pluto.

From Idea to Immortality

But how did an 11-year-old come up with such a fitting name? Venetia was no stranger to the stars. She had fond memories of astronomy lessons outside university parks where students molded the sun and planets out of clay, visually and tangibly representing the solar system. These experiences had sown the seeds of cosmic curiosity in her mind.

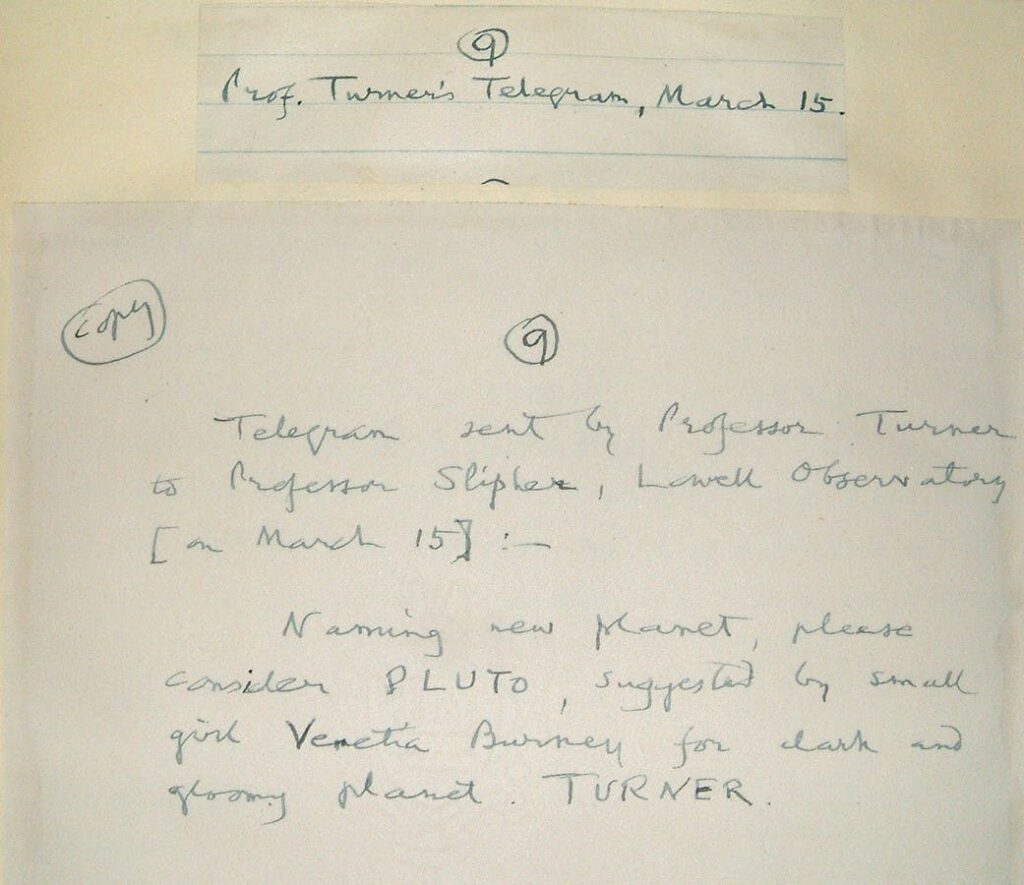

Upon hearing her suggestion, her grandfather, Falconer Madan, didn’t just dismiss it as child’s play. He saw its value. Having spent years surrounded by knowledge at the Bodleian Library, he promptly wrote to Professor Herbert Hall Turner. And Turner, recognizing the merit of the name, ensured it traveled across the Atlantic to the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona.

The name Pluto struck a chord. Besides being the Roman god of the underworld, representing the mysterious characteristics of the new planet, the initials “Pl” were an ode to Percival Lowell, the visionary behind the mission to locate this celestial body.

Destiny or Coincidence?

One might wonder: was Venetia’s suggestion mere coincidence or a stroke of destiny? Whatever it was, the universe seemed to conspire in her favor. Her proposal was more than apt. It was a confluence of mythological relevance, a nod to Percival Lowell, and an intuitive understanding of the planet’s remote nature.

However, not all acknowledged Venetia’s role immediately. Some believed the planet was named after Walt Disney’s dog, but as clarified later, the cartoon dog was inspired by the planet, not the reverse.

The Afterglow of Recognition

Venetia’s newfound fame was met with adoration and some envy. The corridors of her school echoed with whispers and giggles, dubbing her “Plutonia.” And while the limelight faded, her story re-emerged years later in Patrick Moore’s 1984 ‘Sky & Telescope’ article.

Her role in naming Pluto made waves across the Atlantic. American schools, journalists, and space enthusiasts reached out, turning the humble Oxford girl into an astronomical celebrity. Her trip to the Leicester Space Centre’s Sir Patrick Moore Planetarium was particularly notable, where she was celebrated as a living legend.

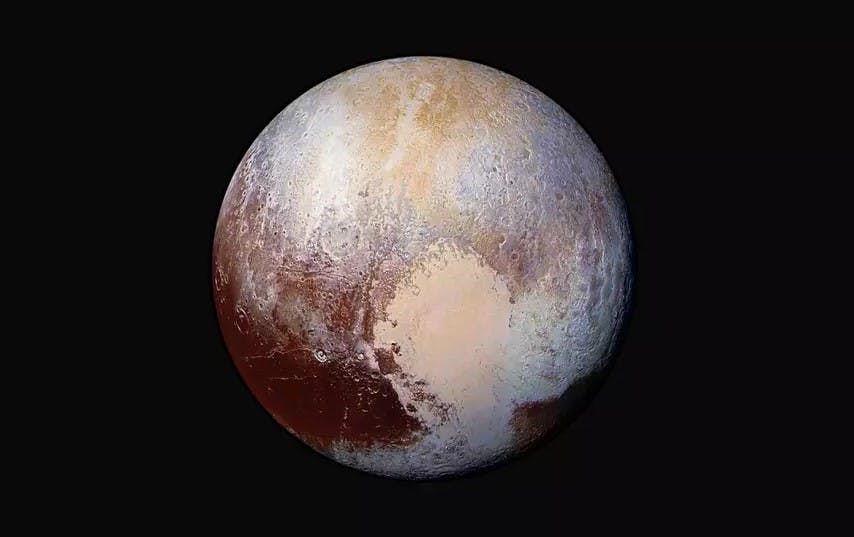

A Celestial Enigma

Although Venetia’s legacy in naming Pluto remains unchallenged, our understanding of the celestial body she named has transformed over the years. Once seen as the ninth and most distant planet from the sun, Pluto is situated within the enigmatic Kuiper Belt. This vast expanse, extending beyond Neptune, teems with numerous icy, rocky bodies larger than 62 miles across and a staggering count of over a trillion comets.

Pluto’s initial discovery was rooted in observations by American astronomer Percival Lowell. In 1905, while monitoring unusual deviations in the orbits of Neptune and Uranus, Lowell hypothesized another planetary entity influencing these deviations. He made predictions of its location in 1915 but passed away a decade and a half before Pluto was eventually identified by Clyde Tombaugh at the Lowell Observatory in 1930.

A Heated Debacle: Why Pluto Lost Its Status

By 2006, Pluto’s classification as a planet came under scrutiny, resulting in its reclassification as a dwarf planet. This change wasn’t universally accepted and triggered intense debates both within and outside the scientific community.

But why did this happen? According to Emily Safron, an astronomy instructor at Case Western Reserve University, as we learned more about the Kuiper Belt, it became evident that Pluto wasn’t as unique as previously thought. Several celestial bodies mirrored Pluto’s characteristics, sometimes even more closely than Pluto mirrored the other traditional planets.

The International Astronomical Union, in an attempt to streamline the definition of a ‘planet’, established three criteria:

The object must orbit the sun.

It must have a sizeable mass to achieve a roughly spherical shape.

It must clear its orbit of similarly massive objects.

While Pluto met the first two conditions, it faltered on the third. Intriguingly, Charon, one of Pluto’s moons, has almost half of its size. Thus, instead of being the smallest entity in the planet category, Pluto found a new identity as the most prominent member of the dwarf planet group.

A Legacy Beyond the Stars

Venetia’s life was more than just being the young girl who named Pluto. Her multifaceted journey saw her don many hats – from a chartered accountant to a teacher of history and economics. And while debates raged on about Pluto’s planetary status, Venetia’s contribution stood unchallenged. She passed away in April 2009, but her story, a tale of curiosity and wonder, will always orbit our consciousness.

Pluto’s journey from being heralded as the ninth planet to its current status as a dwarf planet showcases the ever-evolving nature of scientific understanding. As our telescopes pierce further into the cosmos and our knowledge expands, it’s crucial to remember the joy of discovery, the same joy that an 11-year-old Venetia felt one fateful morning in Oxford.

Today, as we gaze up at the night sky, amidst the myriad stars and galaxies, Pluto twinkles back – a testament to an 11-year-old’s imagination and the enduring power of names.

Additional Facts

Additional Facts

1,188 km

At 1,188 KM in diameter, Pluto is smaller than Earth’s moon.

248 Years

How long one year is on Pluto. It’s elliptical orbit sometimes brings Pluto closer to the sun than Neptune.

153 hours

How long a single day is on Pluto. This is equivalent to 6 Earth days.